Writer/Artist: gosaribaka

Platform: Tapas (ongoing)

Publication Date: May 23, 2022

Rating: Teen

Genre: Fantasy, Drama

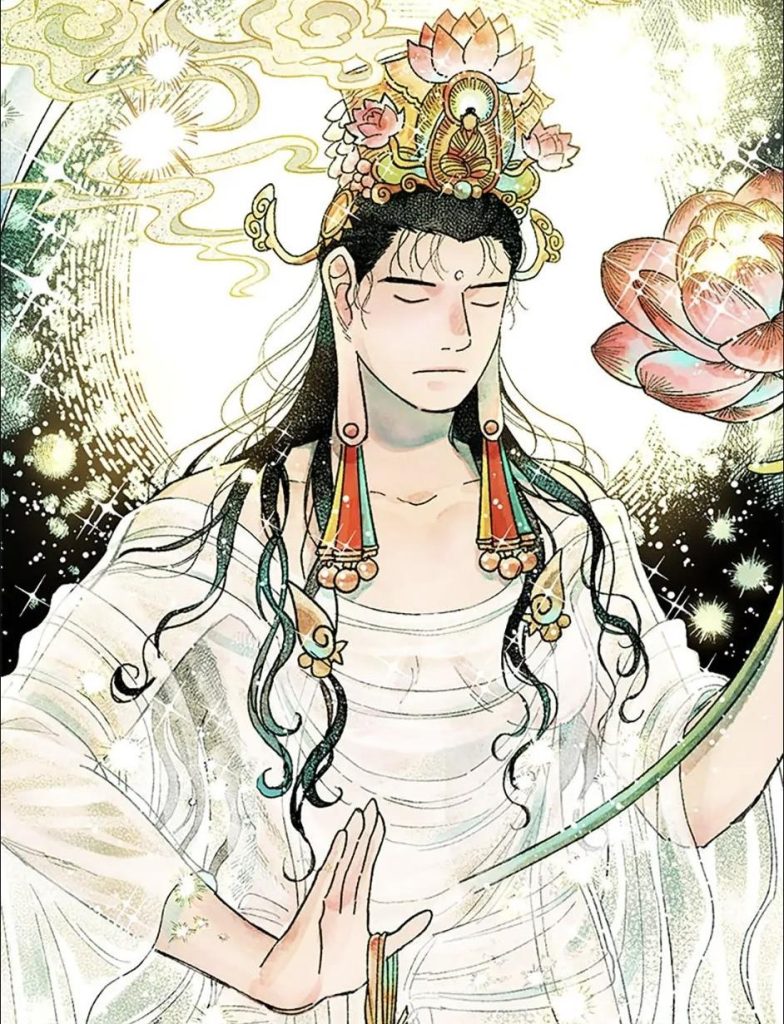

Douyeong is an attendant for Jijang Bosal, the bodhisattva of hell. It is her responsibility to eliminate troublesome gwisins (spirits of the dead) from the human realm. But when she pursues the harmless Dangsam Station Ghost, she runs afoul of the bodhisattva of humans, Guaneum Bosal. Guaneum Bosal restores the Ghost, once a young woman named Park Ja-eon, to life. Then she transports Ja-eon back in time to relive her senior year of high school. It is up to Douyeong to ensure that by the end of that year, Ja-eon achieves enlightenment and enters paradise.

A hurricane of proper nouns

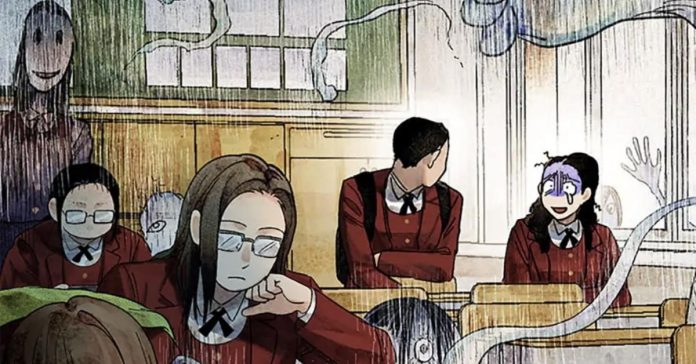

Rebirth in Paradise begins with a hurricane of proper nouns and concepts. As somebody who thought they were familiar with Buddhism, I found myself struggling to keep up. It doesn’t help that the protagonist of the story, Ja-eon, isn’t properly introduced until the second chapter. Once the series switched registers from religious fantasy to school life drama, though, I warmed up to it immediately.

Stories in which the protagonist is reborn into another world or another life have become increasingly popular. I can understand why; what adult wouldn’t want to go back in time and correct the mistakes they made as a teenager? Unfortunately these stories rarely appeal to me. Partly because the genre so often lends itself to wish fulfillment fantasies. But also because, as far as I’m concerned, being a teenager means making mistakes. Reliving those years would be a curse as much as a blessing.

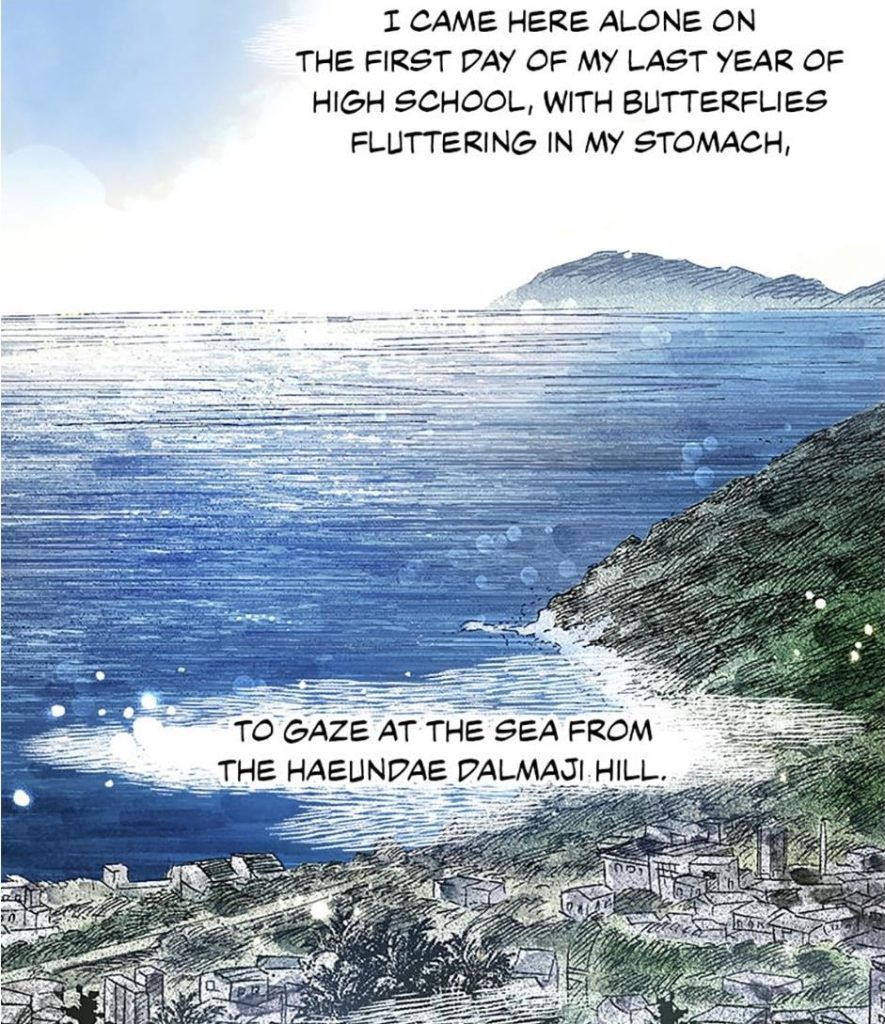

The sea in their hearts

I suspect that the artist gosaribaka shares my ambivalence. At first Ja-eon is overjoyed to return to her youth in Busan. “People who were born by the sea,” she says, “carry the sea in their hearts for the rest of their lives. But now! I’m headed for the sea!” Then she sees her CSAT textbook the next day, and remembers everything that once frustrated her: daily academic pressure, her strained relationship with her mother, the classmates she grew apart from and the long dark tunnel of late adolescence. Rebirth in Paradise allows room for nostalgia, but refuses to sugarcoat these tumultuous years.

Throughout the series, Ja-eon asks herself such questions as: what determines which memories we remember and which we forget? Is it possible to understand another person’s feelings? What is “compassion” and is there such a thing as having too much or too little of it? This is a comic full of long, impassioned monologues about the meaning of life. A comic where the characters converse frankly about relationships, depression and human loneliness.

Humans and bosals

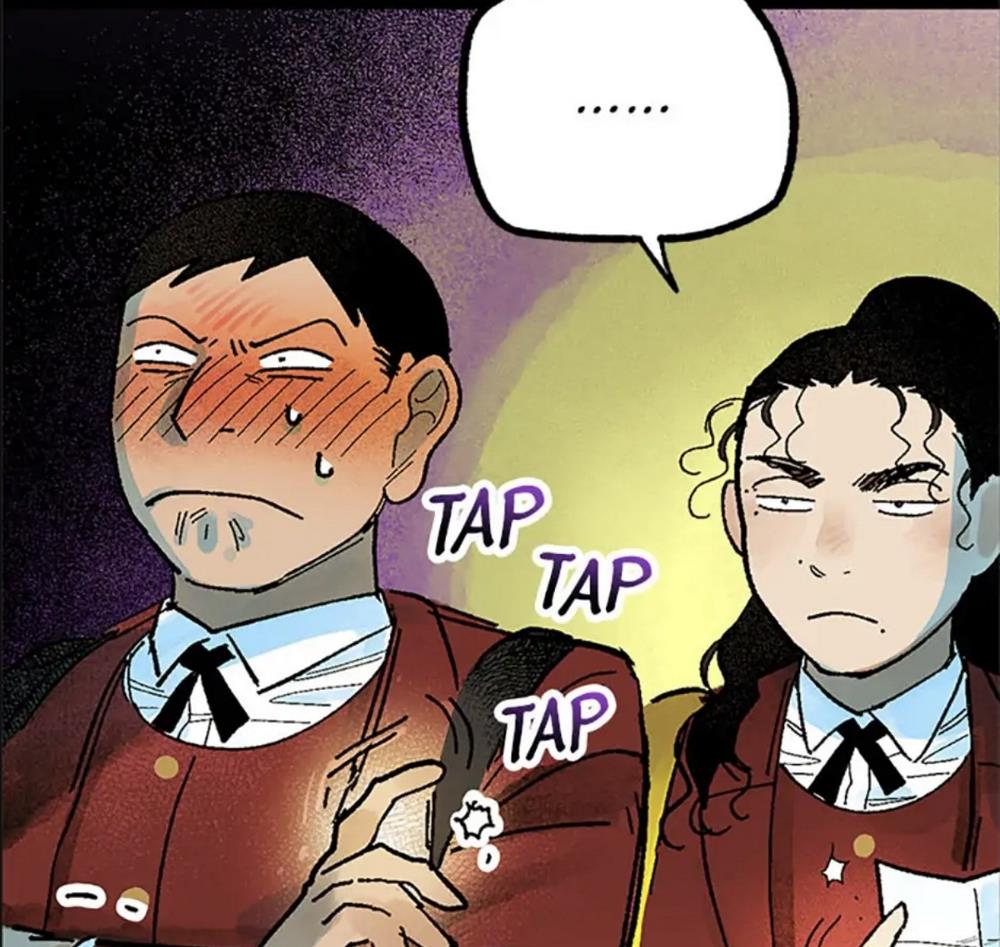

Ja-eon is an appealing lead. Her kindness leads her to go out of her way to help others, but also makes her an easy mark for supernatural forces. Her guardian Douyeong can be headstrong, but is driven not by violence but by the need to be respected and liked for her work. The two of them are great foils for each other. Complicating their relationship is Munsu Bosal, the “Bosal of Supreme Wisdom” and a major player in Rebirth in Paradise’s cosmology. She’s a trickster that makes trouble for her own ends; she’s also self-hating and deeply traumatized.

gosaribaka draws women across the spectrum of body size, shape and form. Douyeong is big and bulky. Her Buddhist colleagues are bald. Ja-eon’s mother and teachers look like real older women in Korea rather than the glamorous actors which populate Korean comics. At the same time, there are very few men throughout Rebirth in Paradise. Bodhisattvas often portrayed as male, like Gwaneum Bosal, are flipped to female here. Of course, bodhisattvas have their own history of gender fluidity. Rebirth in Paradise is just another step of that process of reinterpretation.

“I’m a romantic cat!”

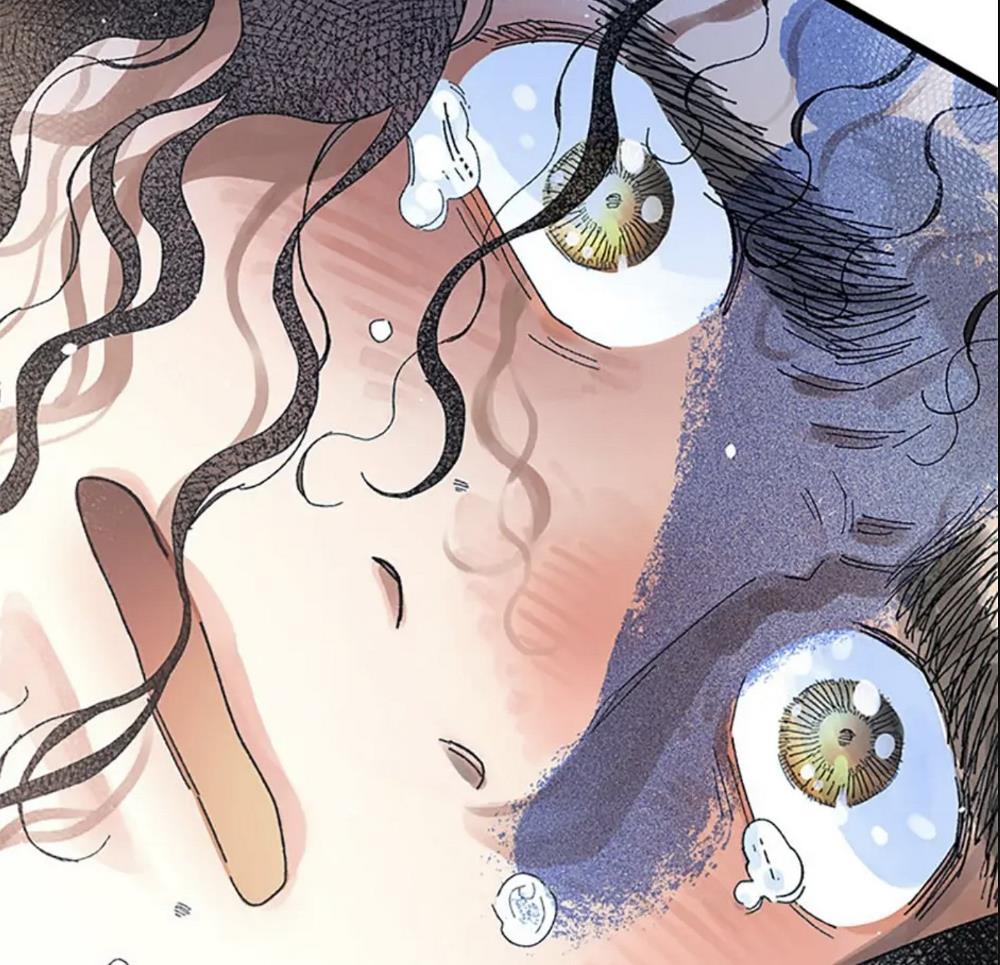

gosaribaka also draws particularly good and emotive faces. Ja-eon’s acting in particular is strong enough that her feelings track from panel to panel despite relatively minor changes in expression. As the series continues, gosaribaka leans on full-screen faces at the expense of physical blocking or backgrounds. There’s a clear shift from the luxurious linework and environments of early chapters to later backgrounds derived from photographs and 3D shapes. That said, gosaribaka retains my favorite trick: underlining speech bubbles with watercolors to set the mood for each scene.

Rebirth in Paradise at its best evokes the cosmic awe of Daisuke Igarashi (Witches) and the raw feeling of Ching Nakamura (Gunjo.) Even when the series falls short of these highs, it carries through with strong dialogue and a mythos that engages with religious iconography rather than blandly replicating it. I’d recommend the comic to any fan of urban fantasy stories with a feminist bent.