Moon Inho is a Korean manhwa artist who has spent his twenty-year career drawing educational comics for children. Last year, he presented a panel at Otakon about the history of those comics together with cultural educator Park Seulki Rhea. This year, he designed Bada, a shapeshifting tiger-girl mascot to represent Korean culture at the convention.

On Sunday morning, the last day of Otakon, Moon Inho ran a panel called “From Korean Folklore to Mascots: Creating Animal Mascot Characters.” As somebody who enjoyed Moon’s previous panel and had fun interviewing him last year, I knew that I had to be there. What surprised me, though, was the singular focus of his panel: tigers.

The images in this panel are adapted from the PowerPoint slides shown at the “From Korean Folklore to Mascots: Creating Animal Mascot Characters” panel run at Otakon by Moon Inho.

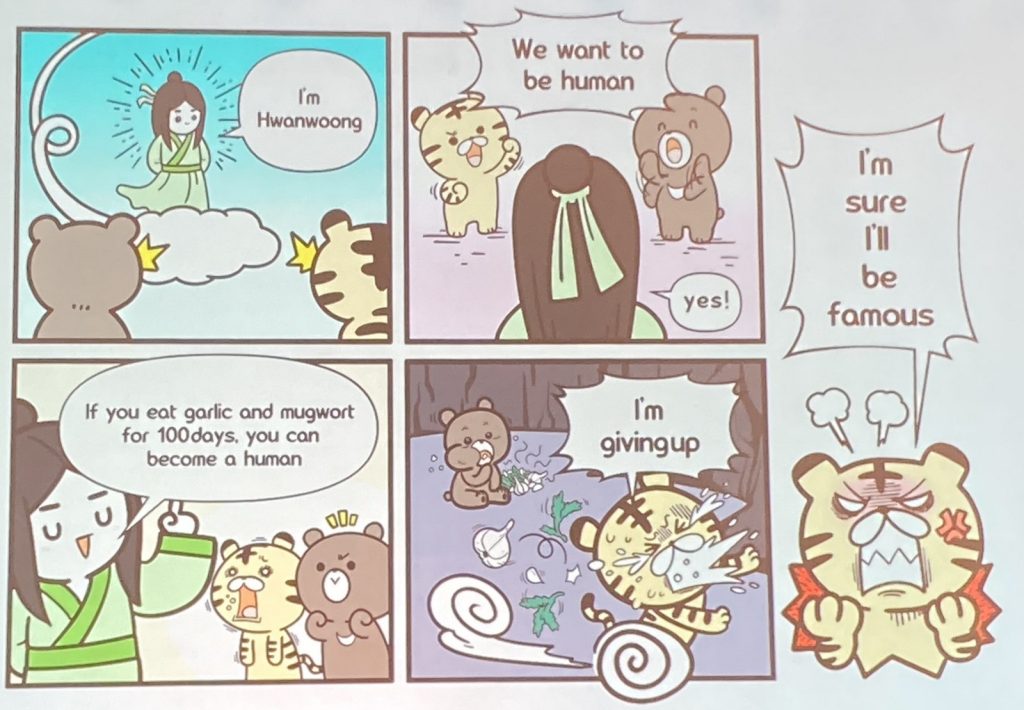

I’m sure I’ll be famous

“In Korea,” Moon said through an interpreter, “a tiger is not a simple creature. It has a very symbolic meaning.” As an example, he told a story of the country’s founding. A tiger and a bear sought out the “Supreme Divine Regent” Hwanung and declared that they wanted to be human. This was within Hwanung’s power. But he insisted that the tiger and the bear endure a test: 100 sunless days, with only garlic and mugwort for sustenance.

The tiger acted hastily and gave up, while the bear persevered and transformed into a human woman. She and Hwanung married and later had a child named Dangun, the founder of Gojoseon and the first king of the Korean peninsula.

According to legend, the Korean government descends directly from the bear. Yet it is the tiger, not the bear, that persists in folklore. Why is this? Well, tigers are visually striking, with their orange fur and black stripes. They are also very dangerous. Traditional folk paintings depict tigers maiming and killing people. The character for tiger (which is also used for leopards) reads as “ferocious beasts.”

Power!! Power!!

In the Joseon era, tigers came to the royal palace to attack people. The government formed a special forces group to chase and catch them. They reportedly possessed outstanding skill on the battlefield and went on to inspire many webtoons, games, and TV dramas (including the BTS-linked webtoon 7FATES: CHAKHO).

For a more recent example, Moon Inho brought up an advertisement from the 1990s. “In the past,” this video reportedly said, “we in Korea were threatened by tigers and smallpox. Now, modern children face the terrifying consequence of becoming delinquents and distributing illegal videos!”

So yes, tigers were feared. Yet they were also revered. Tigers were mountain protectors and companions of local gods. People wore tiger talismans to protect themselves from ghosts. In this way, a tiger’s power could both help and hurt.

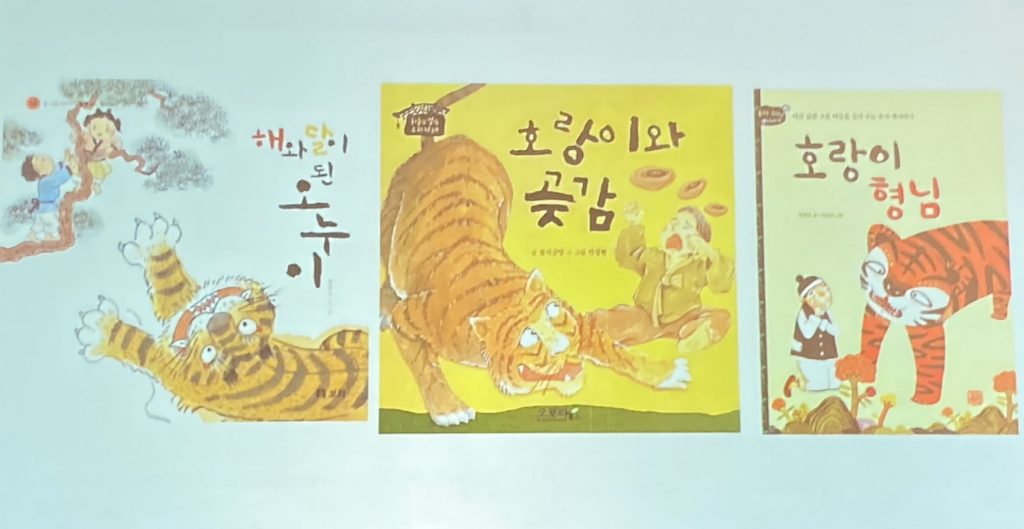

Three folk tales

Moon Inho told three classic folk tales presenting the tiger in different modes. In the first, “The Two Siblings Who Became the Sun and the Moon,” the tiger is a villain. It pesters a working mother for rice cakes, eats her when the rice cakes run out, and then steals her clothes to try and eat her children as well. The children pray to heaven for aid and are rewarded by a rope to the skies; they become the sun and the moon. The tiger, by comparison, falls from the rope and dies. It’s a story that should be familiar to folks who know “Red Riding Hood” or “Jack and the Beanstalk.”

Another story, “The Tiger and the Persimmon,” spins the tiger as a comedic figure. It comes down from the mountains in search of a meal and finds a crying child. The child’s mother says, “If you keep crying, the tiger will eat you!” (To which the tiger says, “Yes, that’s right.”) When the mother shuts her kid up by offering them a persimmon, though, the tiger is shocked. “What is a persimmon?” it asks itself. “If it made this child stop crying, it must be even scarier than myself.” The tiger fails because it doesn’t recognize the fruit.

In the third story, “Brother Tiger,” a tiger finds a woodsman living with his mother. The woodsman tricks the tiger into thinking that he was once his human brother, who transformed while wandering the woods. The tiger then goes out to catch food for his new family. Rather than a monster or a buffoon, he is portrayed as a “faithful son,” a change from how tigers were represented in the other two stories.

The tiger and the magpie

Tigers also appear frequently in Korean proverbs, or sokdam. The most famous might be “the days of tiger smoking,” which means something like “a long time ago.” Other sayings include “even if you are bitten by a tiger, you will live if you keep your head up;” “you have to go to a tiger’s den to catch a tiger cub;” and “speak of the tiger, and he will come.” (As opposed to the devil or Cao Cao, depending on your literary tradition.)

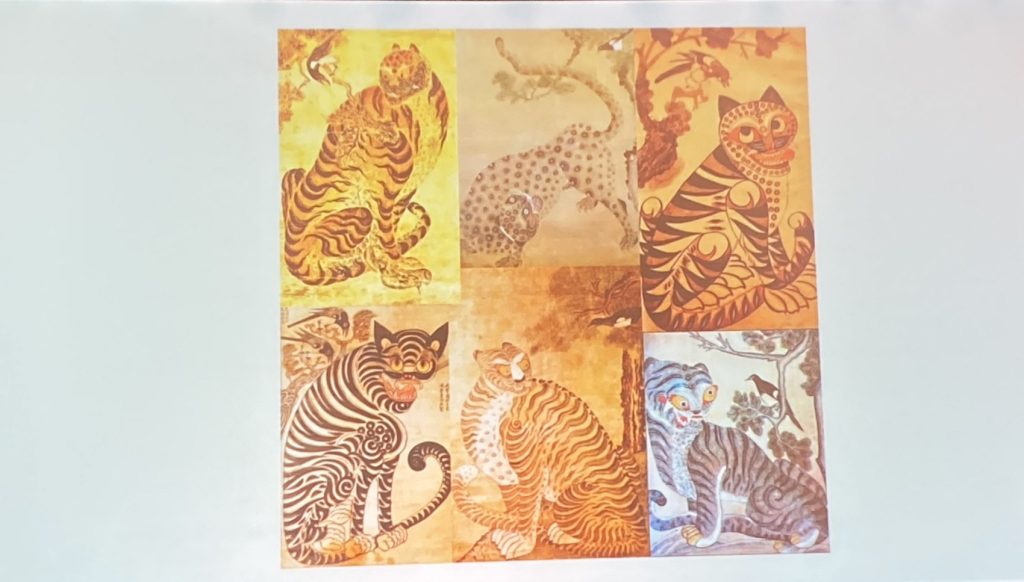

The recent animated film KPop Demon Hunters also features tigers. Derpy, the pet of demon bad boy Jinu, is a fluffy purple tiger creature who can travel through solid surfaces. Derpy is accompanied by Sussie, a perpetually frowning magpie who is fed up with the big cat’s antics. Keen-eyed viewers will recognize that Derpy and Sussie represent the tiger and magpie, an animal pair that recurs in a genre of drawing called hojakdo.

Aside from their aesthetics, hojakdo were a form of class commentary. Tigers represented the ruling class, who were drawn to their power and prestige. Magpies became shorthand for the common people. Despite the strength of the tiger, it was really the magpie that made fun of them and caused them grief.

Those are its two faces

Later, designers used tigers as mascots. One example was Hodori, the mascot of the 1988 Seoul Olympics. Another is Soohorang, who represented the PyeongChang Winter Olympics in 2018. (Its partner was Bandabi, a bear.) Aside from sports, MUZIK TIGER is a well-known brand in South Korea that features small, cute tigers prominently.

“In the hearts of the Korean people,” Moon Inho said, “the tiger is still a ferocious character, but can also be a friend. Those are its two faces.” That is why Bada, Otakon’s Korean mascot, has two forms. One is a Siberian tiger, meant to represent one of the four deities (its peers are the dragon, bird, and tortoise). The other is that of a ten-year-old girl. Even when she is in human form, though, Bada is very powerful—after all, she is an up-and-coming K-Pop idol! Her heightened sense of taste and smell also makes her a great candidate for the world of mukbang influencer culture (also known as food vlogging).

A tiger’s many sides

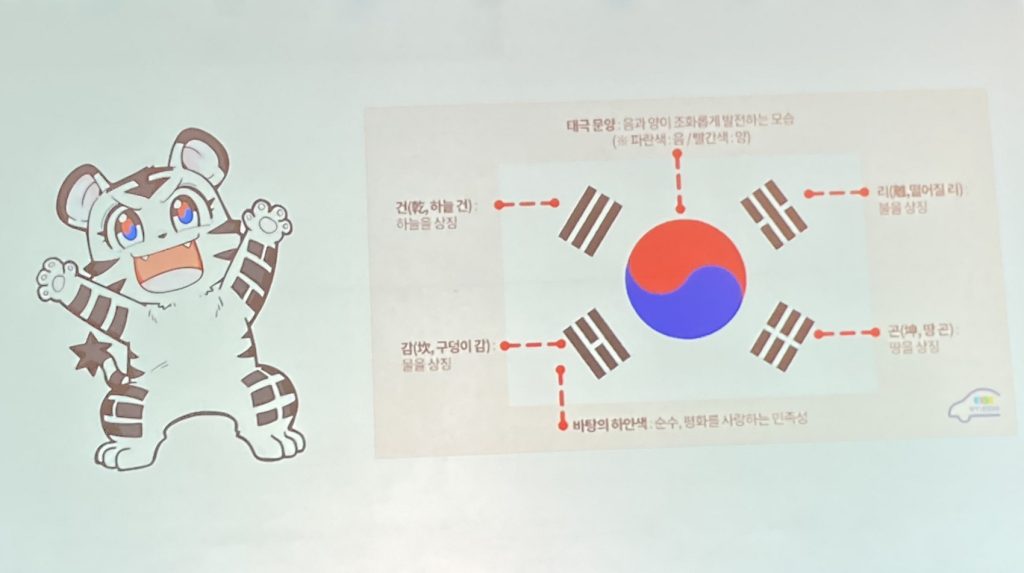

Moon Inho made sure to represent different parts of the Korean tradition in Bada’s design. Bada’s eyes use the blue and red of the Taegeuk, the orb in the middle of the Korean flag. That flag’s rays in the corners can be seen in Bada’s stripes. Just like Korea has many sides, Bada has many sides to her, too. A tiger is not just a monster.

Not that there are tigers left in Korea anymore. The last of them was reportedly killed in the 1940s. (That’s assuming there aren’t a few still hiding in Korea’s Demilitarized Zone, which is currently home to over 6000 animal and plant species.) The Korean government reintroduced the tiger’s old friend, the bear, to Jirisan in 2004. But the fears of the public (as well as the significant amount of land required for tigers to live and thrive) make it unlikely that tigers might follow suit.

Tigers can still be found today, if rarely, in countries like India, Thailand, and Bhutan. Perhaps the same might one day be true on the Korean peninsula. Until then, the only surviving remnants of Korean tigers are fictional: Derpy, Hodori, and (of course) Bada.

Source: Otakon