Continuing my France – Japan travel diary with Day 1 in Paris. You can see my entry for Day 0 – Day 1, which has some of my past travel mishaps and travel tips. Now on to the actual comics/manga part of the trip!

Day 1 (continued) – Bande dessinée, 1964 – 2024 exhibit at Pompidou Centre, Paris

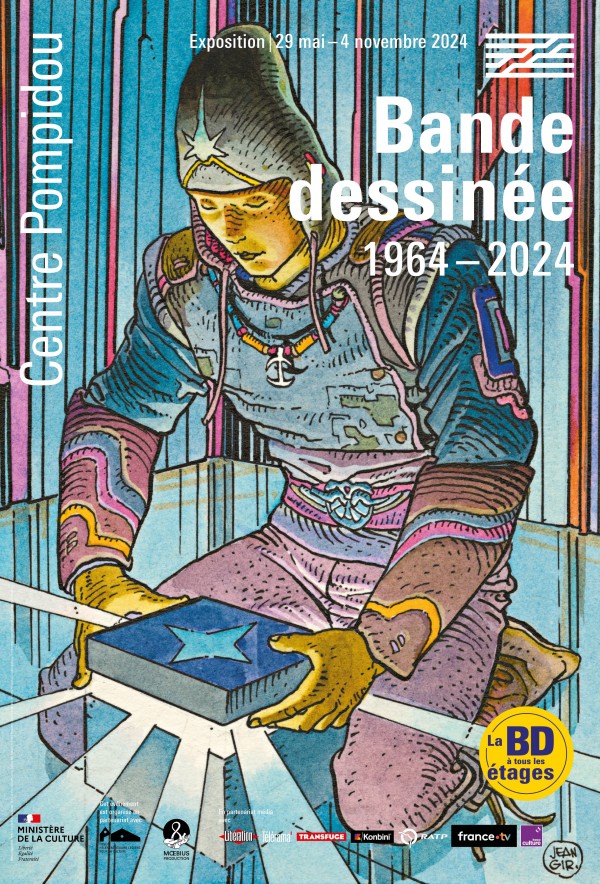

After arriving in Paris, I dropped off my bags at my hotel, and walked to Pompidou Centre to visit the Bande dessinée (Comics) 1964-2024 exhibit. This exhibit opened in late May 2024, and was part of the various events and cultural activities in the City of Light to celebrate the 2024 Olympics.

Compared to the US, France treats comics like a distinctive form of cultural expression that is valued alongside music, literature, sculpture, painting and drawing, architecture, theater, and media arts (radio, television, photography). I knew that are referred to as “the 9th art,” but I was surprised to see that there’s a 10th art as well: video games and digital arts.

Comics being singled out as a valued art form in France really something special. You see this level of respect and government funding/support for comics in Japan and maybe S. Korea, but not so much in the US, where comics exhibits and museums dedicated to comics and comics creators are relatively rare.

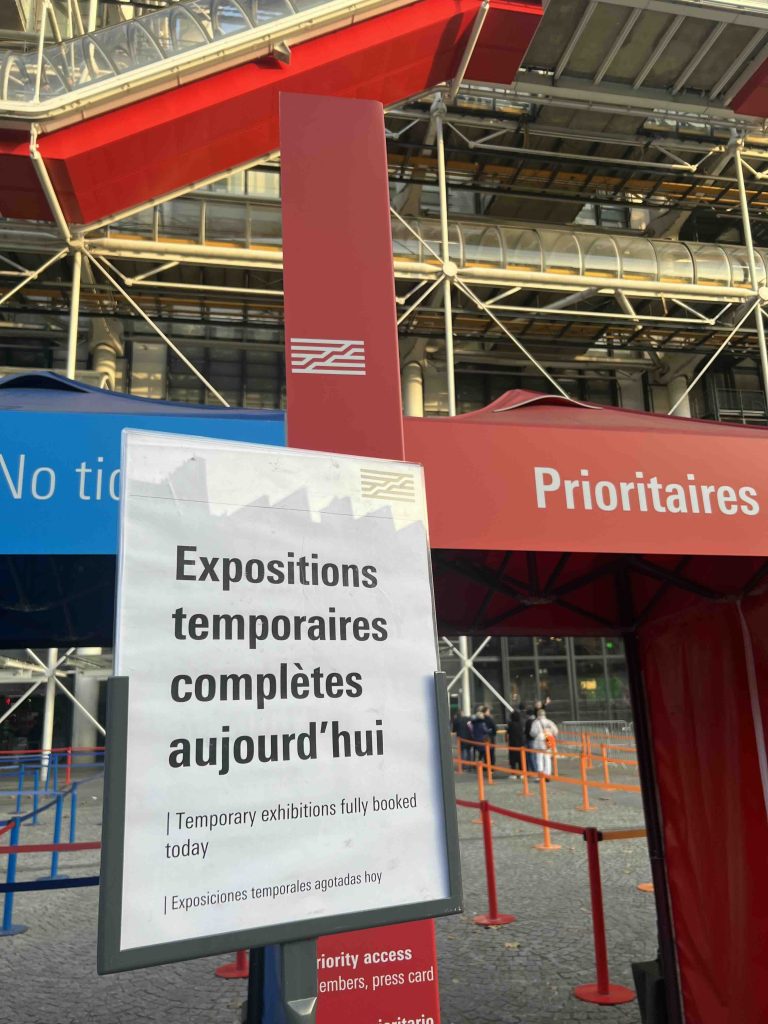

I was so grateful that I bought tickets for this exhibit ahead of time because there was a sign at the door saying that “today’s tickets for temporary exhibits were sold out.” This was extra important because the last day of the exhibit would be Monday, November 4, and Sunday was my only full day in Paris. I made a point to arrive in Paris this weekend because I really, really wanted to see this show in person, so it would have been a huge bummer to come all this way and be turned away at the door.

Rule 6 for France Travel: Book tickets for museums and attractions in advance

Many popular museums and attractions in France offer online ticketing. Even if the museum/attraction isn’t sold out, these advance purchase tickets often let you avoid long lines to enter (The Louvre Museum is a prime example of this).

Rule 6.1 for France Travel: Libraries are bookstores, bibliotheques are libraries.

One thing that always trips me up a bit when I’m in France: a “librairie” is a bookstore. A “bibliotheque” is a library. Why do I bring this up? Well!

I’ve visited the Pompidou Centre before, but it was only on this trip that I realized that it’s not just an art museum that has exhibits, lectures, and film screenings – it’s also a huge public library! When I arrived just around 12:30 pm, there was a long line of mostly young adults (teens – 20-somethings) leading to the “Bibliotheque BPI” door. I didn’t think much of it, until I visited the Hugo Pratt / Corto Maltese comics exhibit, which was on Floor 3 in the middle of the library.

What an amazing sight – people lining up to get into a public library! A really nice, well-stocked library, but still! When’s the last time you’ve seen something like that in the US?

I’ll get back to the Corto Maltese exhibit in a bit. First, the main reason why I’m here: The Bande Dessinee 1964-2024 exhibit!

Floor 5: Bande Desinee 1964 – 2024: BD, Manga, Comics and More

After taking several escalators up to the 5th floor of the Pompidou Centre, I began my comics journey of this amazing exhibit.

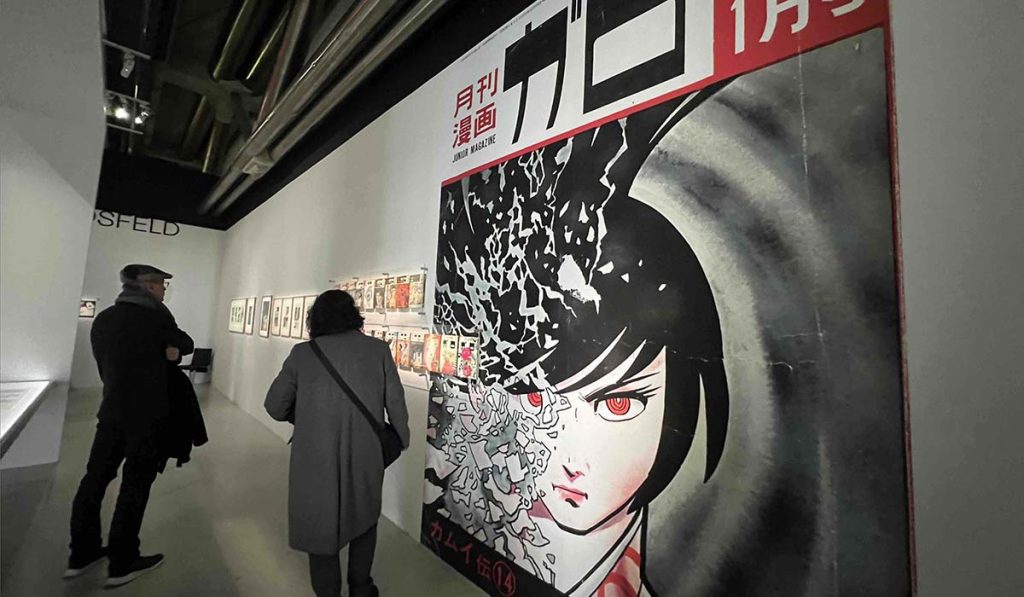

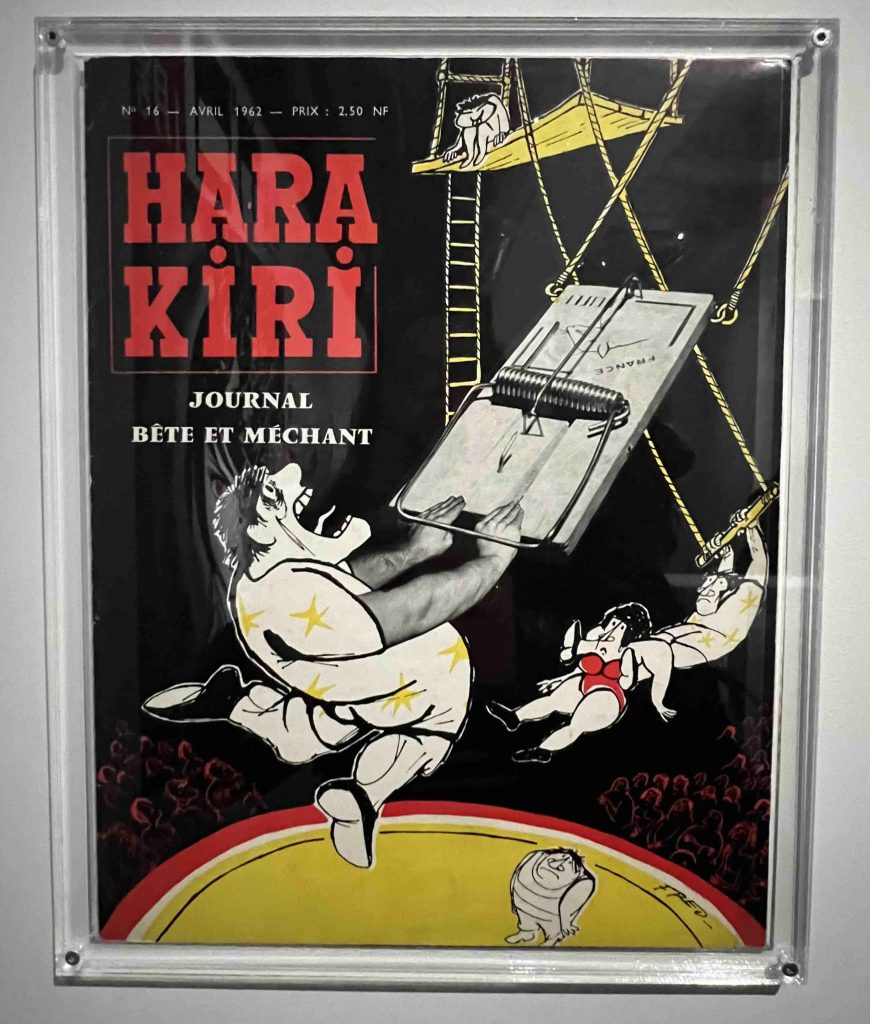

So why is the exhibit starting from 1964, especially since comics as a popular art form in France/Belgium, N. America and Japan existed before 1964? The first room of the exhibit answered that question – as it spotlighted comics and counterculture as it emerged and flowered in the tumultuous times we know as the mid-late 1960s.

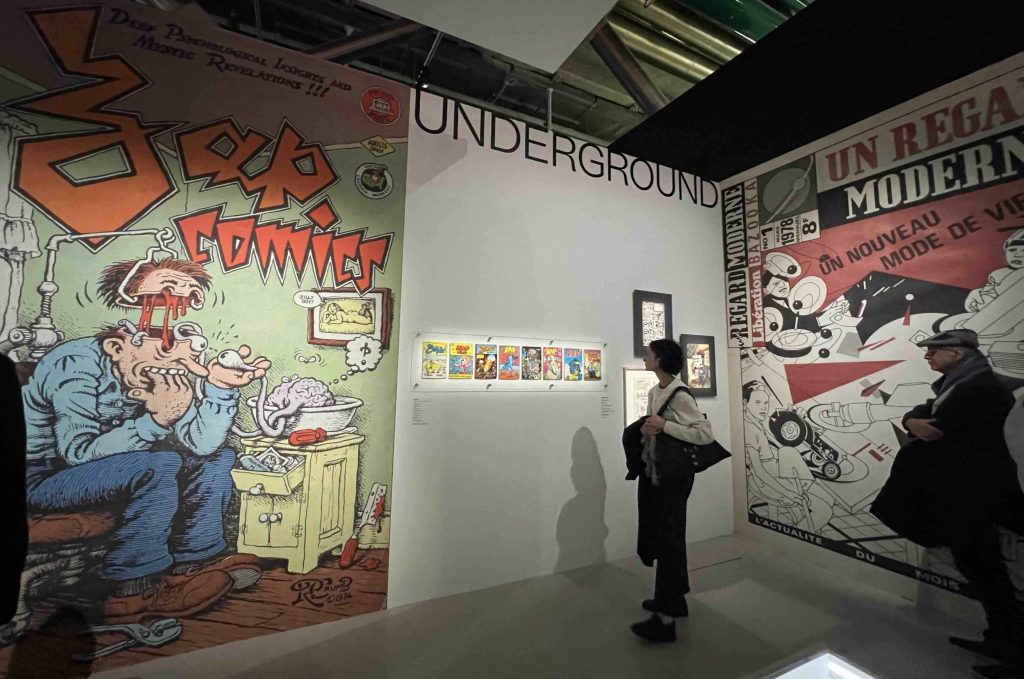

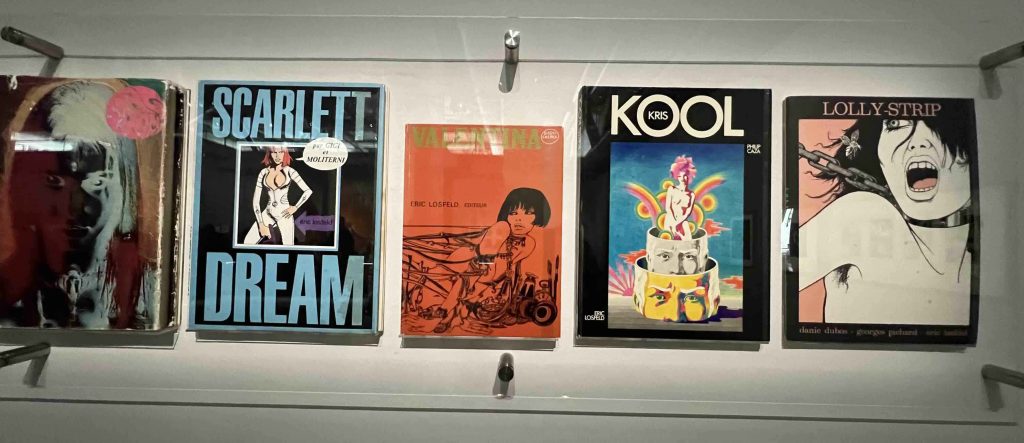

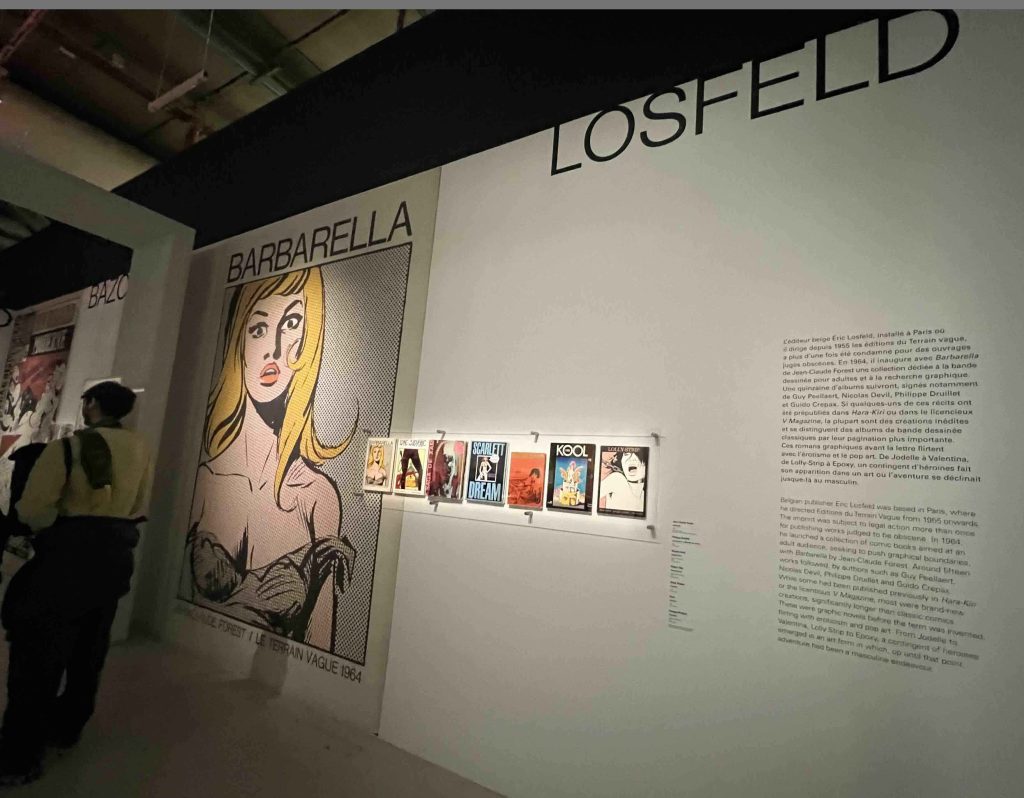

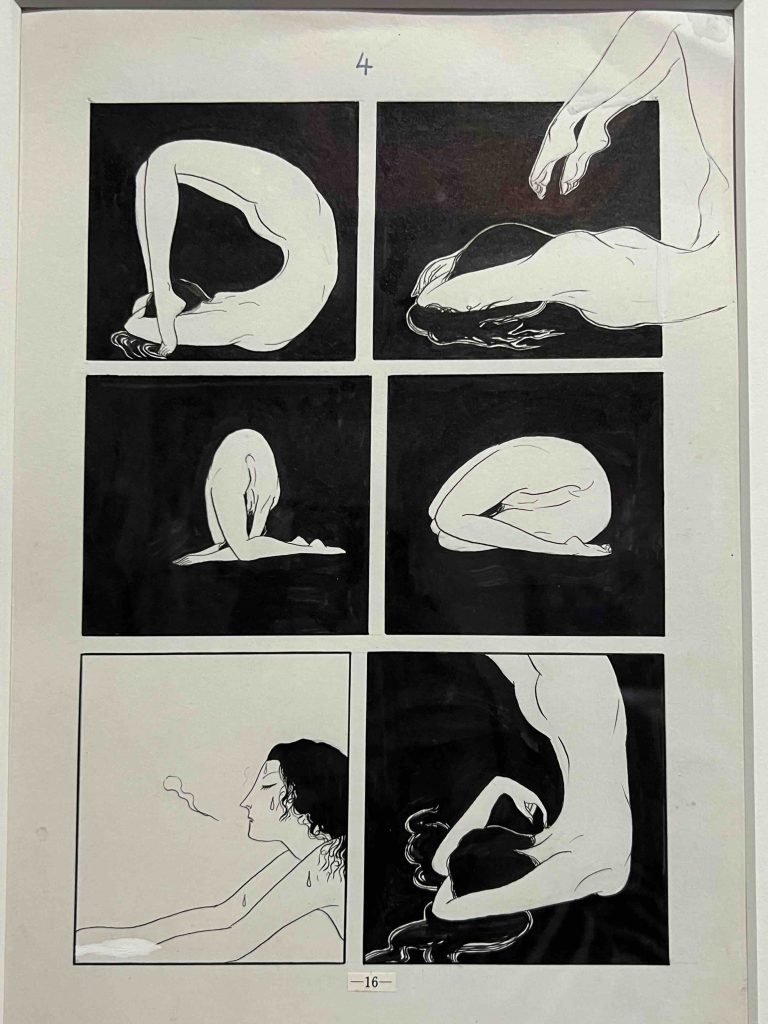

In this first room, each of the four walls were dedicated to dedicated to ground-breaking comics magazines that pushed the boundaries of comics beyond being just “entertainment for kids.” French magazines like Hara-Kiri satirized politics and culture, while Belgian/French publisher Eric Losfeld put out graphic novels aimed at adult readers, like sci-fi erotic fantasy-adventure Barbarella by Jean-Claude Forest (available in English from Humanoids) and Valentina by Guido Crepax (available as part of The Complete Crepax series from Fantagraphics).

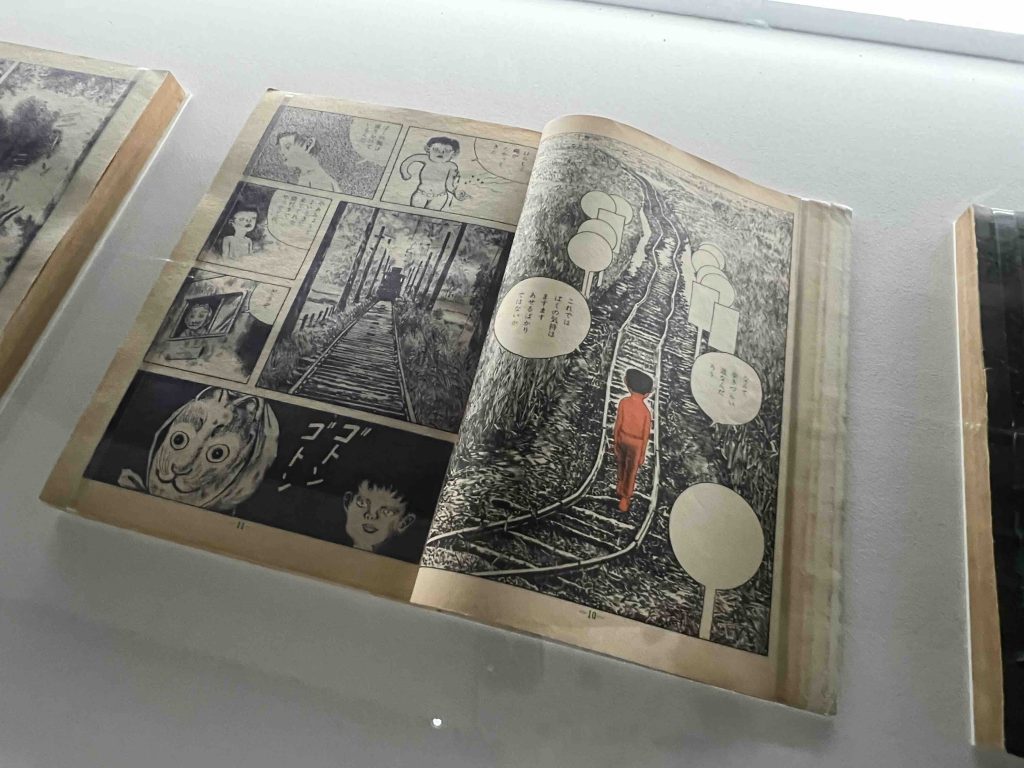

Meanwhile, half a world away, Japanese avant-garde manga magazine GARO was breaking new ground with stories like Kamui-Den by Sanpei Shirato, a story about ninjas set in feudal-era Japan that offered vivid critiques of class inequality that resonated strongly with college students. (The original Legend of Kamui story will be available in English from D&Q in January 2025)

If you love the manga that Drawn and Quarterly is publishing in English, the “Counterculture” room at this exhibit will have you swooning. Besides examples by indie manga legend Yoshiharu Tsuge (Nejishiki), there were also original pages by Susumu Katsumata (Red Colored Elegy), Kuniko Tsurita (The Sky is Blue with a Single Cloud), along with Yoshiro Tatsumi (A Drifting Life and Abandon the Old in Tokyo) and yokai manga icon Shigeru Mizuki (WWII epic Onwards Towards Our Noble Deaths, Kitaro, and the recently released Yokai art book).

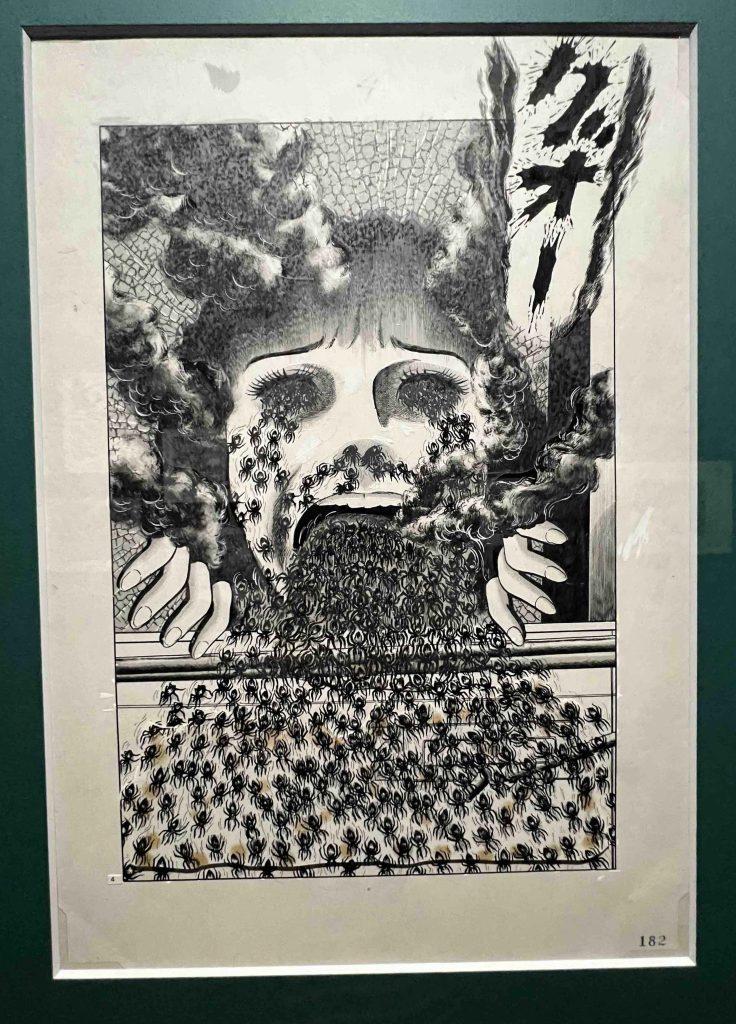

Other manga creators featured prominently in the exhibit include Kazuo Umezz (Drifting Classroom, from VIZ Media), Gou Tanabe (H.P. Lovecraft’s The Shadow Over Innsmouth, available from Dark Horse), Maruo Suehiro (The Strange Tale of Panorama Island) and Yuichi Yokoyama (previously published in English by PictureBox, but out of print now)* but some were noticeably missing for various reasons.

*Editor’s note: Yokoyama’s Plaza is available now from Living the Line.

There were no original pages from AKIRA by Katsuhiro Otomo on display, so they showed a climactic scene from the anime instead. And no Junji Ito in the horror manga section? There’s a good reason for that too, since there was a major retrospective of Junji Ito’s manga at the Setagaya Literary Museum in Tokyo around the same time as this exhibit.

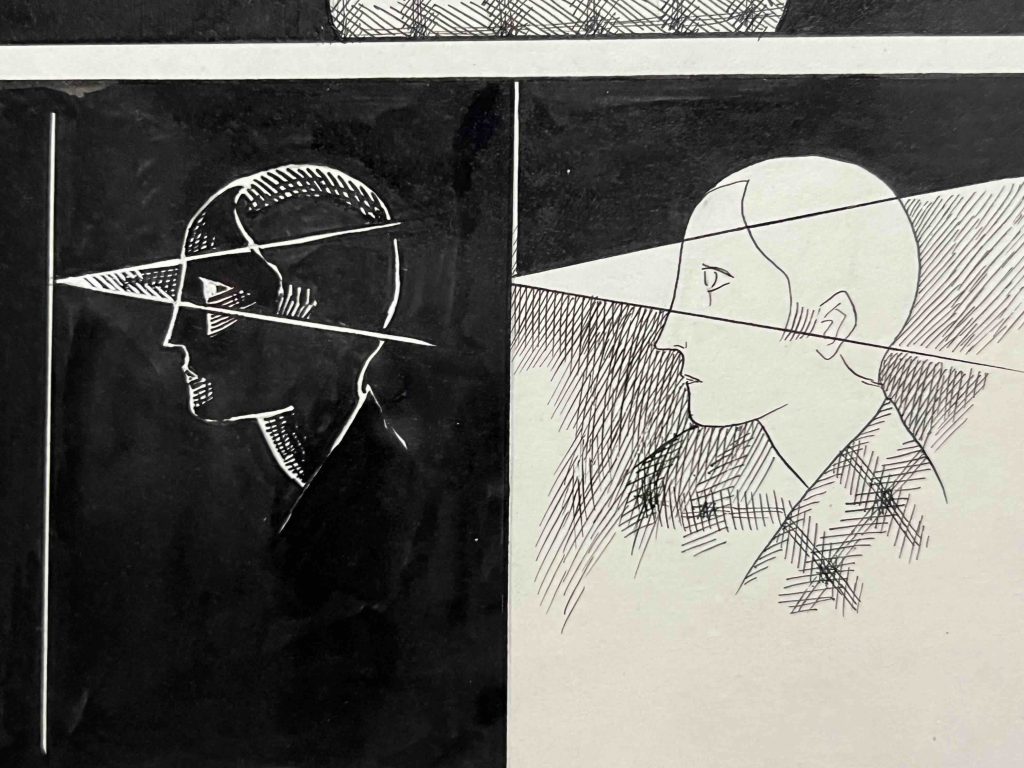

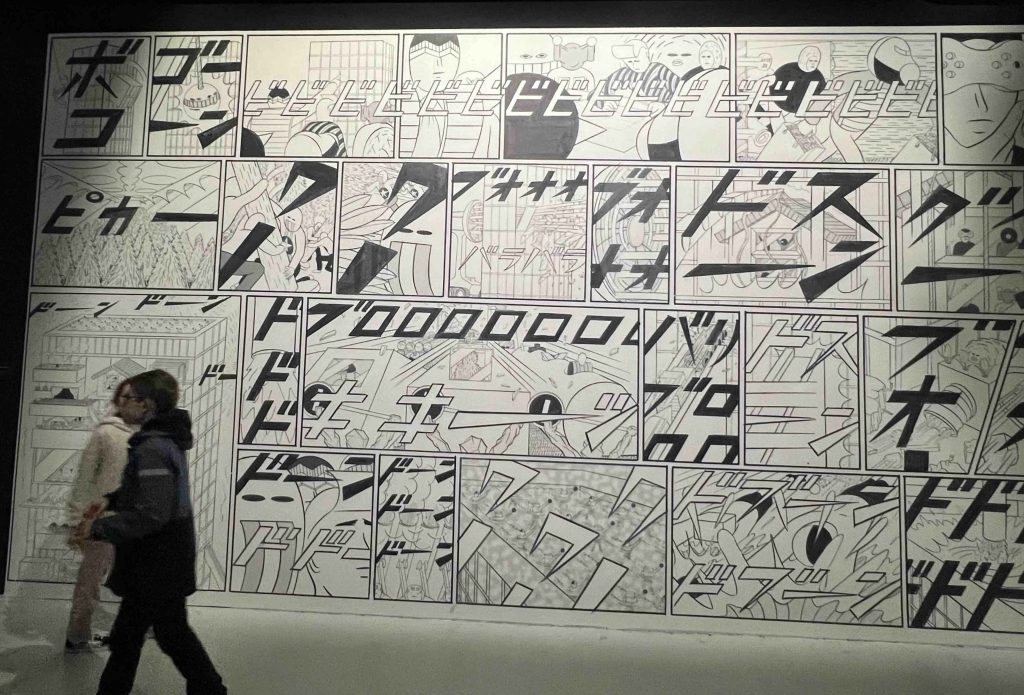

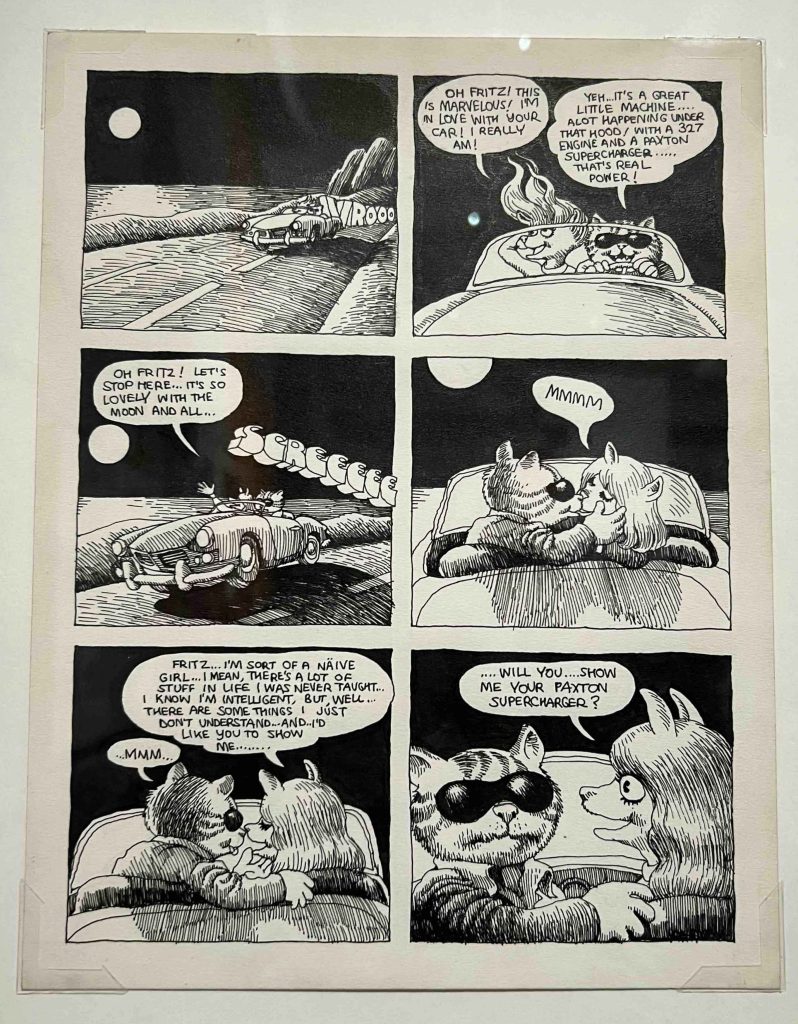

Representing the US underground comics scene were creators first featured in Zap! Comics, like Robert Crumb, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, and Gilbert Shelton (The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers). In all of these displays, there was a mix of printed magazines to show the work as readers then would have experienced them, and original comics pages, where you could see faint pencil marks, ink pen strokes and white-out. It’s magical to see the hand of the artist in each pen and brush stroke, evident even years after these works were first published.

This first room really set the tone for the rest of the exhibit – in each themed room, there would be representative works by comics creators from Europe, Japan, and US/Canada side by side. This allowed visitors to see how creators from different parts of the world tackle topics like humor, horror, science fiction, abstraction, history and war, cities, and autobiography instead of organizing them by date of creation or country of origin.

It also made it clear that this exhibit would mostly focus on comics created for grown-up readers. Yes, there were some examples of comics created for younger readers (especially in the humor section, where Peanuts comics strips by Charles Schulz were displayed next to Doraemon by Fujio Fujiko, Osomatsu-kun by Fujio Akatsuka (only available as a JP-EN bilingual edition) and Asterix by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo (available in English from Papercutz) but based on the people I saw browsing the show on Sunday, I saw almost no one under age 16.

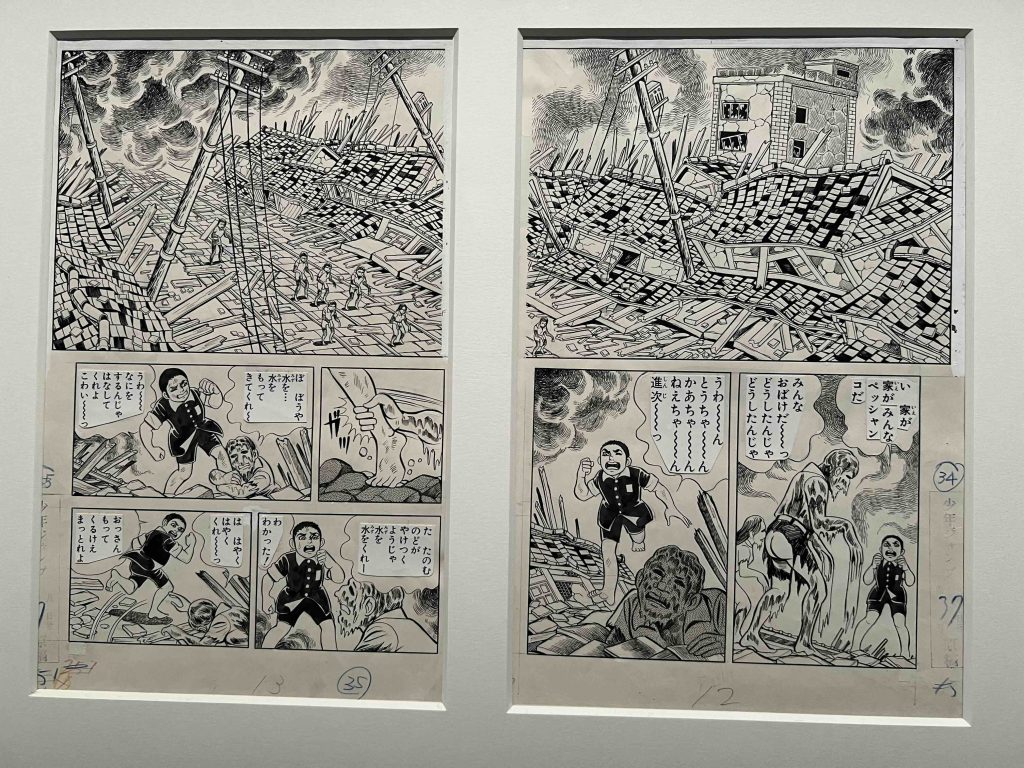

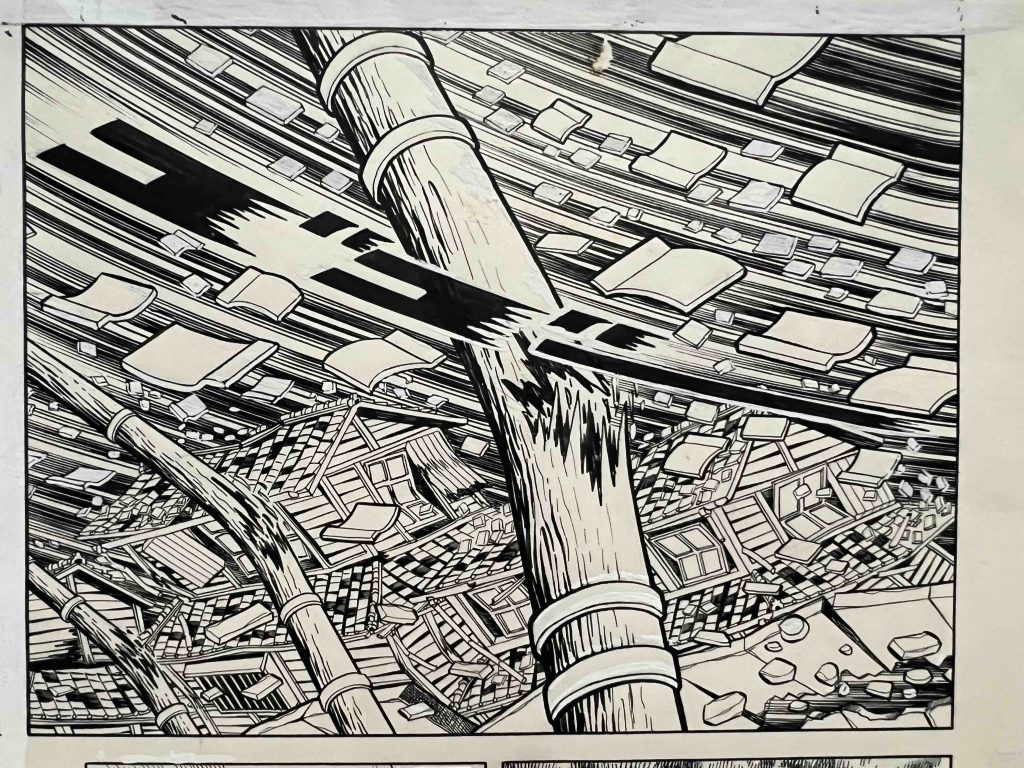

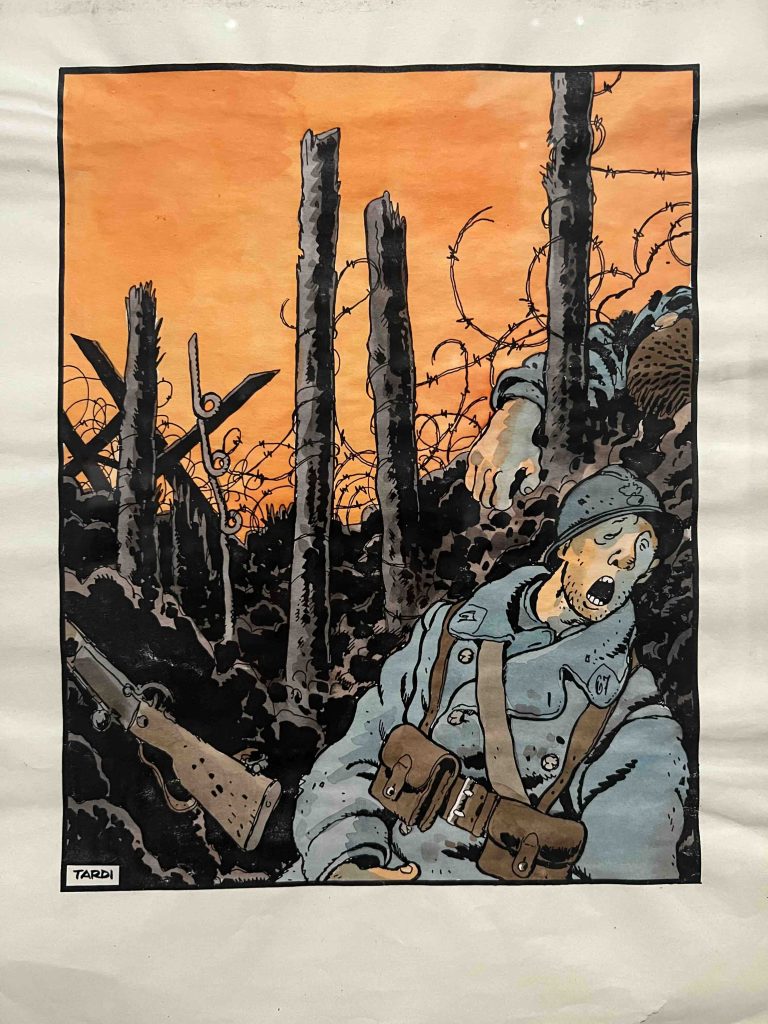

Some of the comics on display, while undeniably gorgeous, would probably be frightening to younger readers, or perhaps would require an adult/parent to guide them through some of the more intense stories on display, like the unforgettable scene of Hiroshima in the immediate aftermath of the atomic bomb from Barefoot Gen by Keiji Nakazawa (available in English from Last Gasp) or wartime scenes from It Was the War of the Trenches by Jacques Tardi and Palestine by Joe Sacco (both available in English from Fantagraphics)

Still, there were many works on display that left a lasting impression.

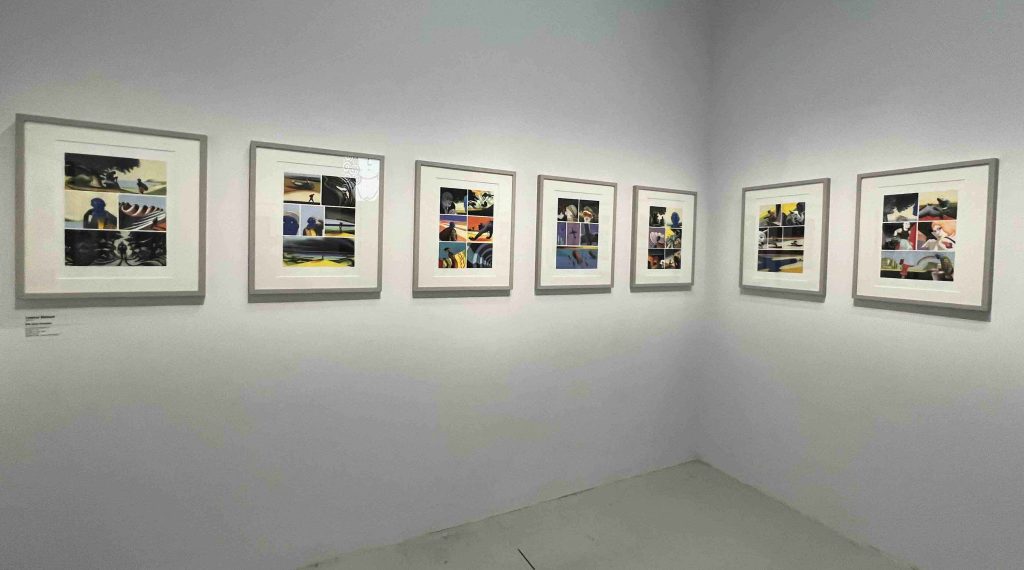

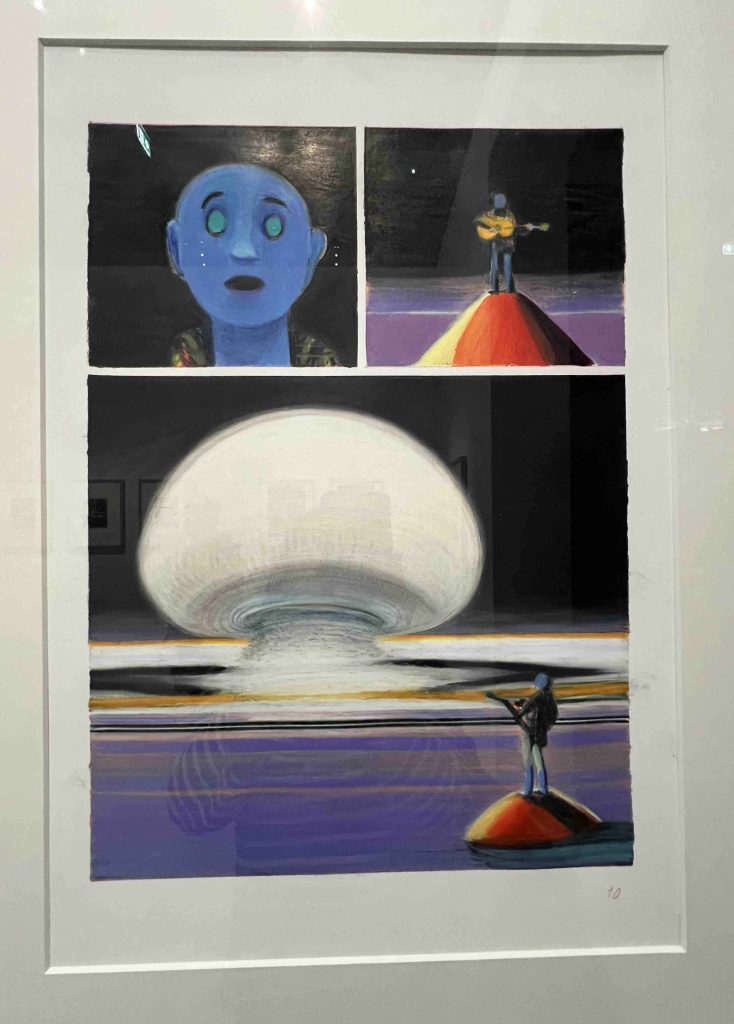

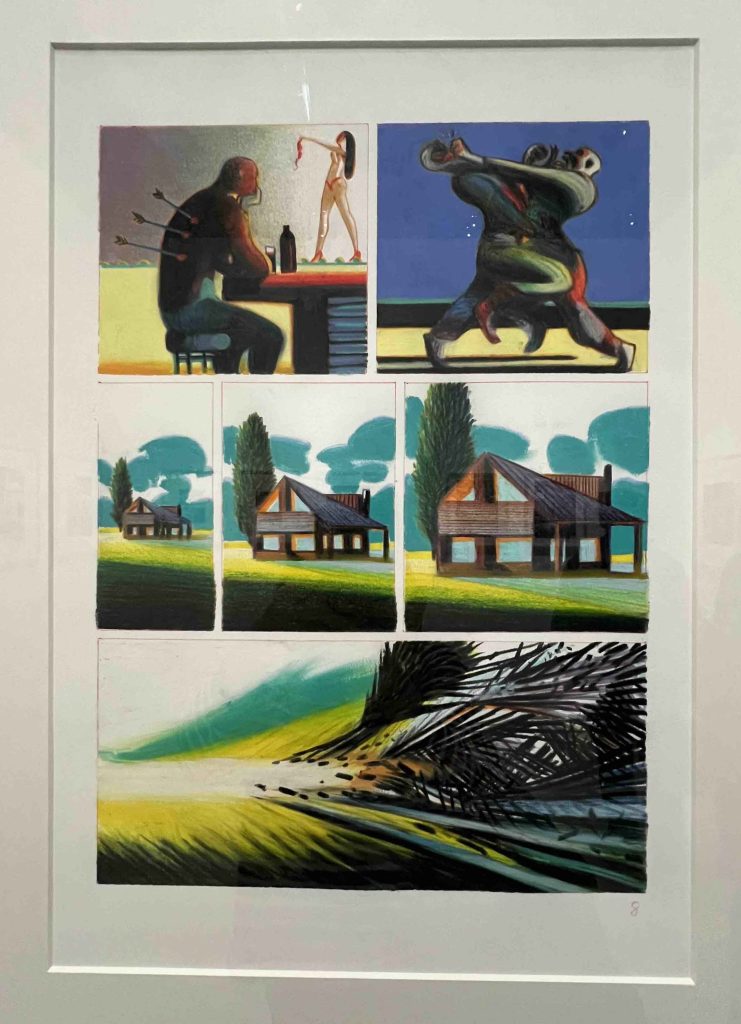

Lorenzo Mattotti’s vivid wordless comic inspired by Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall” was on display while the song played on a loop. As I listened to the song, I could see which part of the lyrics were illustrated by Mattotti in powerful, sometimes unexpected compositions. You could see the beats of the song, especially the chorus depicted by panels showing snapshots of destruction. It’s available in English as part of Bob Dylan Revisited, a 2009 collection of comics inspired his songs. I’m glad it is because I ordered this book immediately.

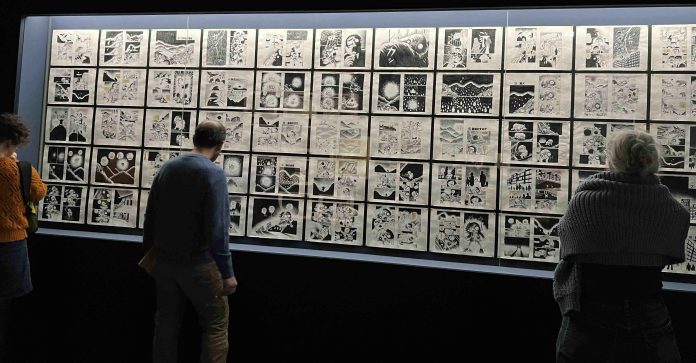

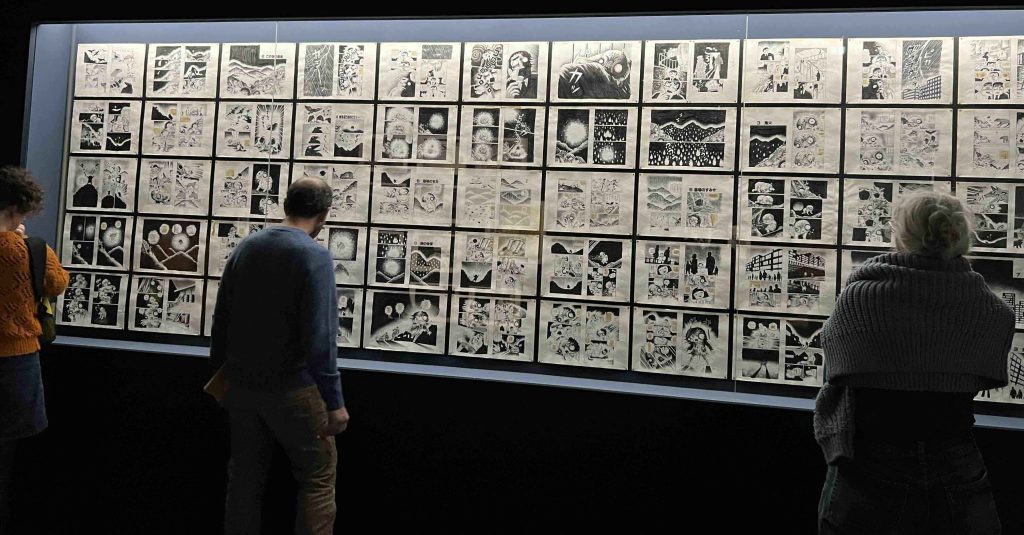

Another standout was a full wall featuring several chapters from Hideshi Hino’s horror masterpiece, Hell Baby, a story about a horribly disfigured baby that was rejected by its father, was influenced by Hino’s experiences with viewing the aftermath of WWII firsthand. It was powerful in that instead of viewing one page of a story as a work of art, you get to see the real essence of comics: the rhythm and impact of sequential storytelling over several pages. While the long-out-of-print Hell Baby hasn’t yet been re-license for English release, indie publisher Star Fruit Books has published other works by Hino, including The Town of Pigs and Panorama of Hell.

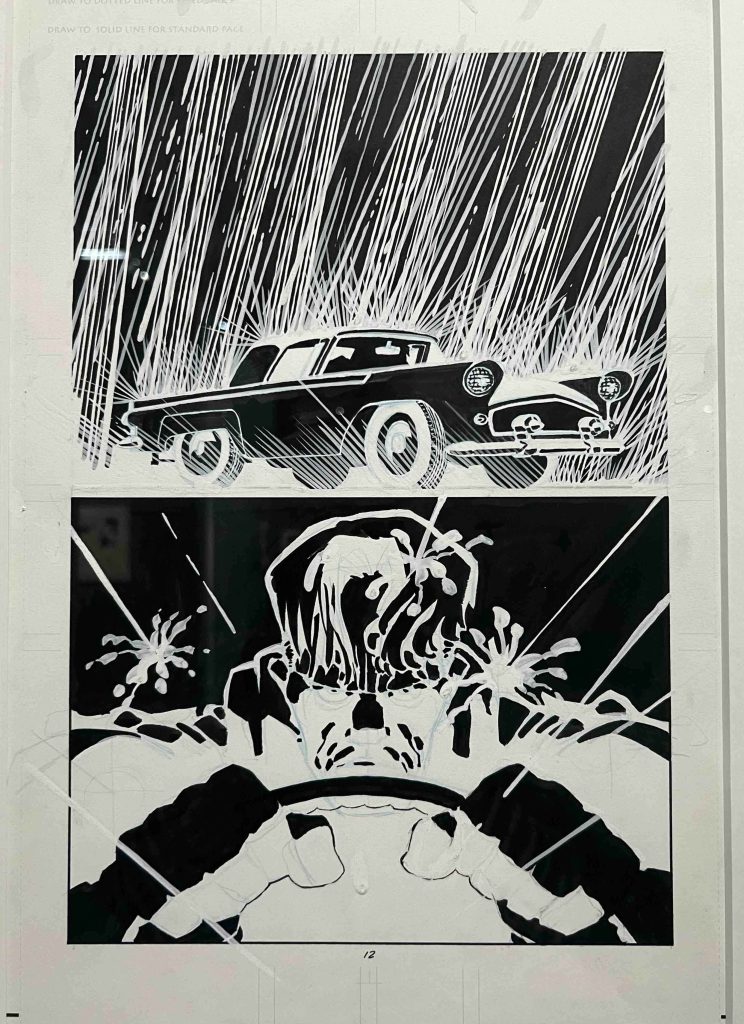

Also stunning to see up close: a few pages from Frank Miller’s noir classic Sin City (available in English from Dark Horse) and a few pages from Alan Moore’s Watchmen drawn by Dave Gibbons (available from DC Comics).

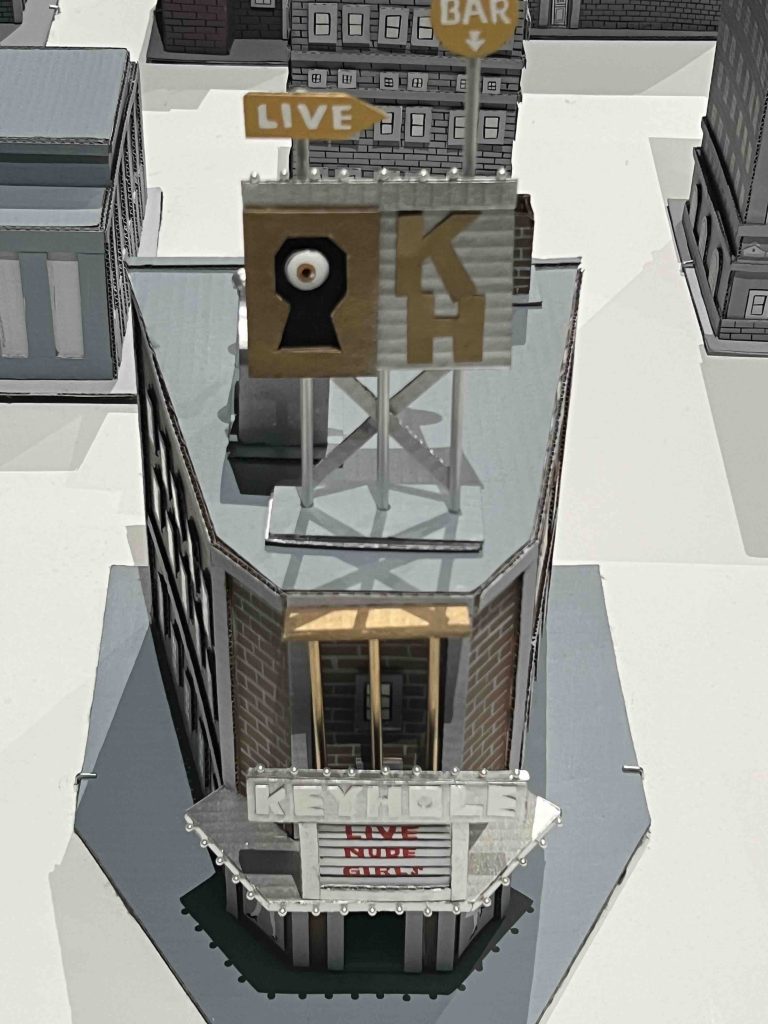

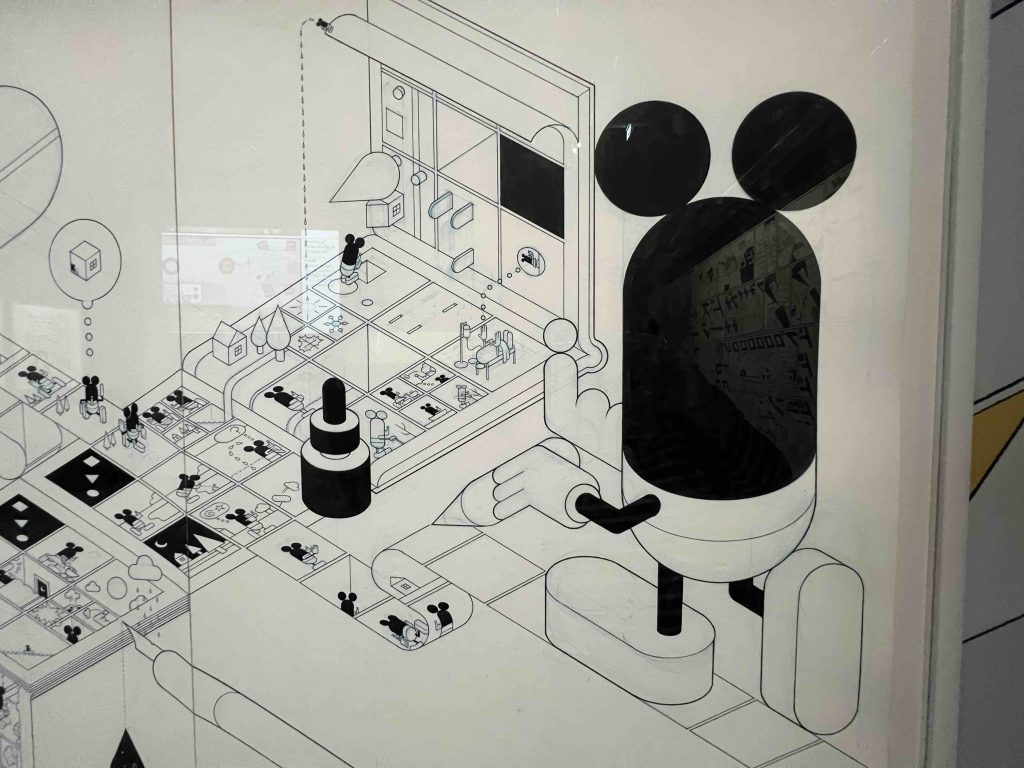

Also, Seth’s cardboard city bringing the world of Clyde Fans (available from D&Q) to life in the “Cities” room was astonishing too.

I do appreciate that the curators took care to include a diverse array of comics creators – male and female, from different countries of origin and different art styles and themes. The act of assembling this all-star line-up of innovative visual storytellers from Europe, Japan, and US/Canada was an incredible accomplishment that won’t be replicated anytime soon.

I learned so much about French-Belgian comics and the very best that they have to offer that it made me almost sad so many amazing European comics stories and creators don’t get the exposure and respect they deserve in N. America. It’s great that publishers like Fantagraphics, Last Gasp, Drawn & Quarterly, Dark Horse, MadCave, Humanoids, NBM and more have been fighting the good fight to bring the most iconic stories by European comics’ masters out in English but clearly, there’s room for more.

It almost feels unfair to mention what was missing from the mix from such an ambitious exhibit, but I’ll say it anyway: why were romance/stories by/for women/girls missing from the mix? And why miss even the slightest mention of works by creators from S. Korea, China, Taiwan and/or Hong Kong?

Of course, the show featured a lot of Franco-Belgian and European creators (as it should, being a comics show in France), but there’s some exciting, innovative things emerging from the Asian comics scene and it’s too bad that there wasn’t room to showcase them. I do understand that it would be almost impossible to cover all aspects of the world of comics in one exhibit, and the curators did a great job bringing together an amazing collection of works that I won’t soon forget. However, as a lifelong fan of shojo manga and someone who’s closely watching what’s happening in the world of Korean comics, I couldn’t help but notice these omissions.

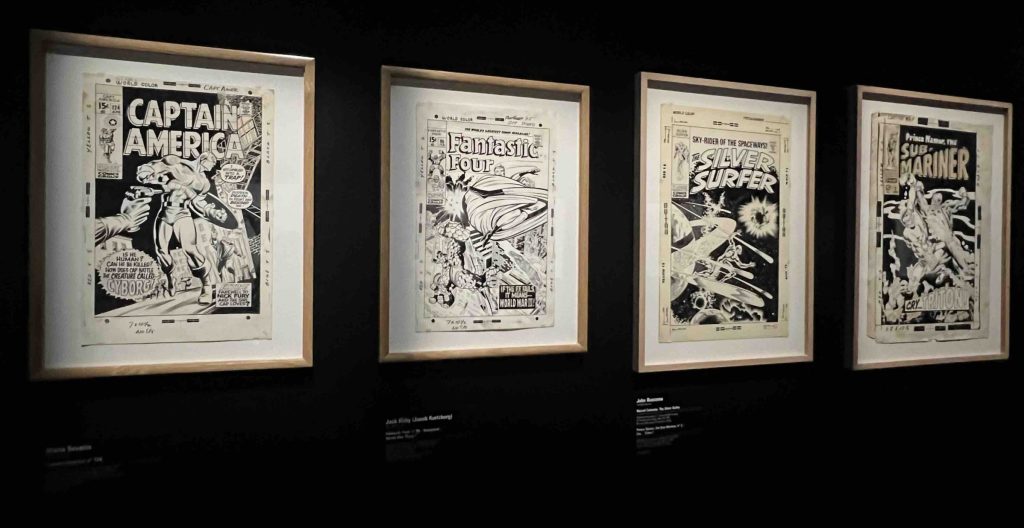

Superhero comics, while a huge part of the N. American comics scene and identity were represented by a few splash pages by Marie Severin, John Buscema and Jack Kirby in the science fiction section, while there was more representation of N. American indie / art comics creators that are Franco-Belgian comics publishing faves, like Dan Clowes (Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron) and Chris Ware (Jimmy Corrigan), Alison Bechdel (Fun Home) and Seth (Clyde Fans) along with pages from MAD Comics superstar Harvey Kurtzman. But nothing from Jaime and Gilbert Hernandez? What a shame.

But these little bits of nit-picking is just me being an Asian American comics fanatic who grew up reading and loving American and Japanese comics – it shouldn’t distract from the incredible collection and thoughtful curation by the exhibit’s organizers, and how it offered a tantalizing glimpse into the amazing world of comics.

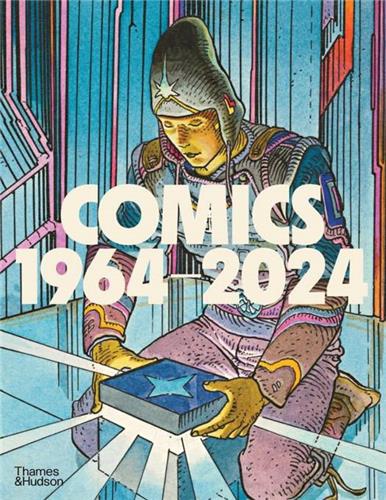

Alas, the day I went to the exhibit was on its last weekend. (Sorry). But you can get a taste of what was on display by picking up the show catalog (a honking brick of an art book, available in English as “Comics 1964-2024” from Thames & Hudson, the same publisher that put out the British Museum Manga exhibit book and the Barbican’s MangAsia exhibit / art book). If you missed out on this exhibit, this is the next best thing to seeing it in person.

There was MORE comics to see at the Pompidou on other floors. I’ll give you a look at these in my next France-Japan travel diary installment.