If you’ve ever needed a ‘through the Looking Glass’ moment, you won’t find many better than Hudson Williams and Connor Storrie carrying the 2026 Winter Olympics torch through the streets of Milan and Cortina. The triumphantly synergetic moment cements Heated Rivalry, the ice hockey romance series that has made them into international stars and queer poster boys, as a cultural phenomenon.

Blink twice, and you could swear that we’ve entered author Rachel Reid’s world where it’s not Williams and Storrie but their characters—pro ice hockey players and secret lovers, Hollander and Rozanov—passing the Olympic flame to each other ahead of competing in the games this February.

For those outside of the increasingly popular yet still niche bubble of romance fiction and its even nicher subset, queer romance fiction, the concept of the ‘gay sports romance’ may have seemingly arrived, suddenly and fully-formed, out of nowhere. A shiny, new toy under the rotting Christmas tree of our dystopian times. (We deserve a little treat, right? Just for a moment?)

But for those with a finger on the racing pulse of the confluence of influences that allowed Heated Rivalry to not only exist, but thrive, it feels more like a natural peak that creators and consumers of its ilk have been carving a path to for decades now.

What’s the origin of gay sports romance?

LGBTQ+ and—more specifically for this article—gay (M/M) stories have, of course, existed forever. The same can be said for romance. Sports and even sports-adjacent stories centered on physical competition, etc are also pretty old. The merging of all three in western novels, however, is fairly new as a definable subgenre.

Heated Rivalry, first published in 2019, is considered a foundational text. We can also point to Him by Sabrina Bowen and Elle Kennedy and Kage by Maris Black, both from 2015, centered on hockey and MMA, respectively.

Outside of prose novels, C.S. Pacat and Johanna the Mad’s comic book series Fence, published by BOOM! Studios from 2017, is an interesting example. Taking place in an elite, all-boys boarding school, it follows rivals Nicholas and Seiji along their journey to become champion fencers.

While there is canonical queer representation in Fence, Nicholas and Seiji’s tension doesn’t explode into anything as sexually explicit as Hollander and Rozanov’s. That isn’t to say that writer Pacat isn’t aware of and doesn’t play heavily with the idea, though. There’s a great deal of ambiguity in how things end for the pair in Fence: Redemption, which was published from 2023-2024.

Pacat said she was not only inspired by her real-life fencing experience in school and love of “joyously” queer stories, but also by the hugely popular sports manga Haikyu!!. This neatly segues us from west to east and, in particular, Japan: the home of beautiful boys playing beautiful sports, Boys’ Love, and where the two overlap.

We can’t talk about gay sports romance without talking about Boys’ Love

Boys’ Love, the subgenre that Heated Rivalry and the other examples I’ve mentioned fall into, is distinctive within the realm of LGBTQ+ media in that it’s traditionally created by and for women. And romance itself is traditionally viewed as a ‘women’s’ genre.

While M/M romance can be found in Japanese art going back hundreds of years, Boys’ Love (also known as yaoi or shōnen-ai) is a modern phenomenon that can be traced back to the 1970s during the emergence of shōjo manga, which also catered to girls and young women, as well as dōjinshi—fan-authored works. (Bara, meanwhile, is the male-authored and -directed equivalent.)

There’s plenty of criticism to be lobbed at the appropriation of gay male culture and representation by those outside of that group. Certainly, heavy stereotyping, conformity to heteronormative roles, normalised sexual assault, and even internalised misogyny can be found across what came to be formalised as the ‘Boys Love’ market in the 1990s. However, BL, shōjo, and dōjinshi were also the only gateways most female authors had into a male-dominated and -focused industry, and established a uniquely female gaze that continues to permeate the wider manga and anime market (and beyond) to this day.

Even non-gay sports media can be pretty gay (…or not gay enough)

Insert a dated ‘no homo’ joke here, but it doesn’t take a rabid fujoshi (BL fan) to see the homoeroticism in sports, especially contact sports like hockey. Heck, the ancient Olympics used to make athletes throw javelins with their junk out. Naked wrestling on a fur rug in front of a fire, anyone?

Sports stories perfectly heighten a lot of the elements we love in romance: enforced boundaries and restrictions, and—by contrast—forced proximity and enclosed, insular spaces; outside and internal pressure; angst; high stakes; team-ups and rivalries… The arc of a great sports story matches the arc of a great romance: the slow build of tension to a big, feel-good release. On a more shallow level, it also requires everyone to be super fit, i.e. hot. And sweaty.

Throwing a gay romance into the mix, especially one between men, works particularly well because there’s a certain pageantry and performative ritualising in male sports. The idea of two men hooking up in this space is even more taboo than it is anywhere else (yes, it’s still taboo in a lot of places) because these are considered highly sacred places of traditional heteronormativity. (I use ‘traditional’ here in a modern sense; we all know those ancient Greeks and Spartans were far more open-minded.)

Therefore, the ‘forbidden love’ thing, one of the most compelling romance tropes ever invented, is at its most potent when all of these elements coalesce. It’s actually surprising that there aren’t more gay sports romances when you think about how well this melting pot blends.

It’s these traits that attract a lot of women, myself included, to sports manga and anime, despite having no interest in whatever sport is being played. Aside from a good story being a good story, no matter what it’s about, there’s a unique thrill in reading and watching really in-shape guys engaged in verbal, physical, emotional, and psychological drama with one another.

Those rippling muscles are bolstered by something else unique to the female gaze—a beautiful face, somewhere between feminine and androgynous; a style called bishōnen. Aside from general vapidity in romance and wider media in general, this style is swooningly apparent in the casting of relative unknowns, Williams and Storrie, in Heated Rivalry. Williams’s smoulder could melt glass. Storrie’s curls are those of a Greek god.

All of these are the reasons I got really into Kuroko’s Basketball without having a clue about basketball, and Free!, a competitive swimming anime so machine-tooled to pull in a female audience I wanted to stick pins in my eyes for falling for the bait of speedo-wearing athletes breaking the water in shimmering slow-mo and nose-to-nose, heated confrontations outside the pool. Sigh.

Another prominent example, skateboarding anime Sk8 The Infinity, became a lightning rod for queer-baiting debates within the anime community in the early 2020s—a time when the term reached its bandying zenith in online media criticism, sometimes founded and sometimes not. Its character designs, intense relationships, and strong queer subtext, whether ‘baiting’ or not, were certainly illustrative of a shift in the market: even things that merely suggest BL can appeal to that demographic.

The search term ‘Is [insert name of male/male-led manga or anime] BL?’ is common on Google. And even media that delivers on this suggestion, like the beloved series Yuri!!! On Ice, was still confused as a faker for not showing enough intimacy between its central pairing.

The Boys’ Love renaissance & future of gay sports romance

The rise of webtoons, manhwa (Korean manga) and donghua (Chinese manga) have given BL and sports romances a new lease on life. In fact, China has its own distinct term and types of BL stories: danmei. Manhwa, in particular, has enjoyed a hugely increased international profile in the last decade, riding the wave of Korean culture—from music to beauty—that has swept across our global monoculture. And the genres and tropes that have always done well for their Japanese equivalent, such as action and romance, prevail in popularity in these digital-first, vertical scrollers.

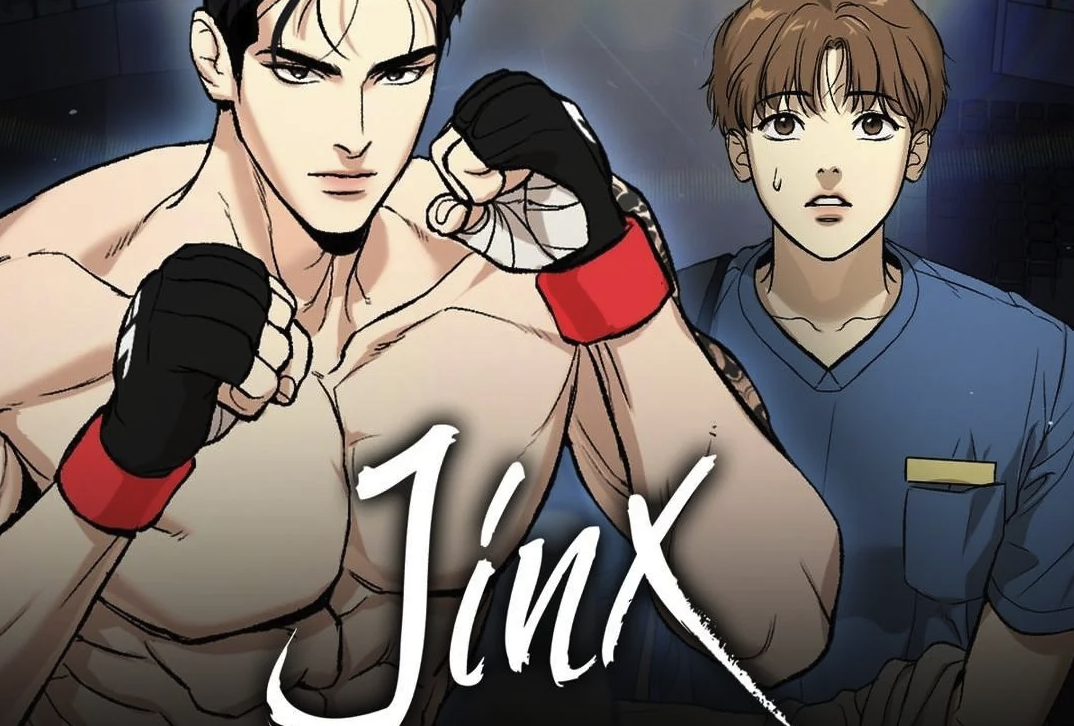

One of the most popular BL sports manhwa, Jinx, authored by BJ Alex’s Mingwa and beginning publication in 2022, is the second-most popular title on English-language platform Lezhin across all genres. It also came in third place in the Japanese BL site Chil-Chil’s 2025 BL Awards.

Jinx centers around an incredibly toxic relationship between an MMA fighter and his physiotherapist. It perfectly epitomizes everything people love and hate about BL: a typically brutish and physically imposing ‘seme’ (top) coercing a smaller, reluctant ‘uke’ (bottom) into a sexual relationship. Consent is dubious, there are virtually no female characters, and LGBTQ+ terms, culture, and themes—beyond sex—are never addressed.

What Jinx does well, other than impressively detailed artwork, is use the framework of competition, the pitfalls of ambition and ego, and the background of repressed trauma to break its male characters down before building them back up.

It’s a far cry from the cosy, cottage-based world of Heated Rivalry, but both series underscore the fantasy appeal of BL vs. the lived-in realism of LGBTQ+ media; exoticism vs. normalization. The steady increase in LGBTQ-inclusive stories around the world—even in places of harsh censorship and prejudice—creates a broad church that caters to all.

In December 2025, while Heated Rivalry fever swept America and Canada, the live-action film adaptation of BL manga 10 Dance became the most-viewed film on Netflix Japan. These recent hits have put BL under the microscope, but it’s also in the spotlight.

Sports protagonists need to lose in the same way romance protagonists need to screw up their relationships and queer protagonists need to (unfortunately) face adversity. The greater the loss, the greater the reward, and if you can hit all three of these pain points, it’s triple the win. In the way sports fans are passionate about their teams, romance fans are passionate about their ‘ships’. Sometimes they’ll let you down, other times they’ll build you up, but you love them all the same.