Nowadays, full-color vertical scrolling webcomics or webtoons are the primary format for comics publishing in S. Korea. But much like manga from Japan, before the webtoon boom, a lot of Korean comics or manhwa were primarily published as black and white line art for print publication. While full-color comics are most of what you see, there are several examples of powerful black and white comics storytelling in K-comics available in English, including the works of Choi Gyu-seok (최규석).

Choi is the award-winning manhwa creator of horror series The Hellbound (co-authored with Yeon Sang-ho, and published in English by Dark Horse Comics), and now The Awl (송곳), which is available now in English from Ablaze.

Born in 1977 in Jinju, South Gyeongsang Province, Choi studied illustration and animation at Sang Myung University and made his debut as a cartoonist in 1998. He has since received numerous honors, including an award from the Dong-LG International Festival of Comics, Cartoon, Character Design and Animation (DIFECA) for The Cola Man in 2002, and was invited to the Angouleme International Comics Festival in France in 2003.

In 2015, The Awl was adapted into a 12 episode live-action television series in 2015, and in 2018, it received the Grand Prize at the Bucheon Comics Awards, as part of the Bucheon International Comics Festival.

Initially serialized on Naver WEBTOON in S. Korea from 2013 – 2018, The Awl is a dramatic yet very real story about the labor movement there as it was in the late 2000s. The events depicted in this six volume graphic novel series are based on a true story that happened in 2007, when temporary workers were fired at a retail store. This led to a sit-in protest that lasted more than 500 days.

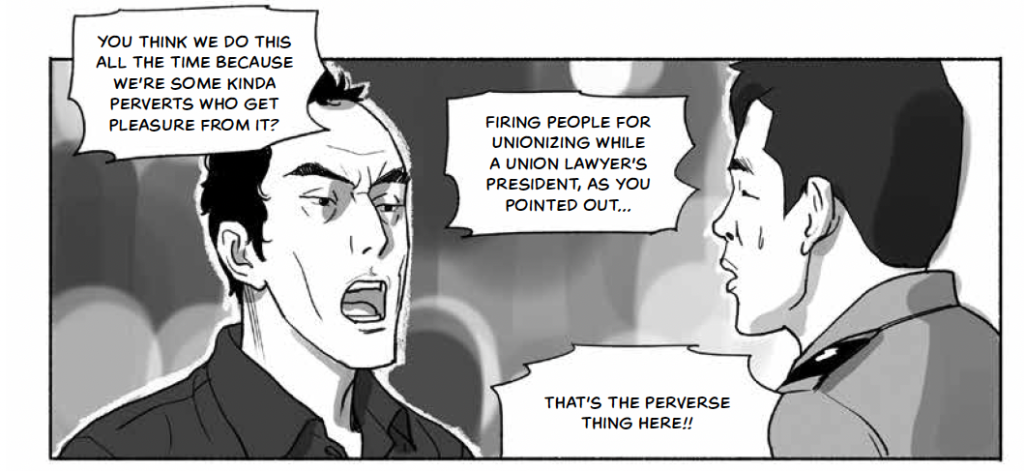

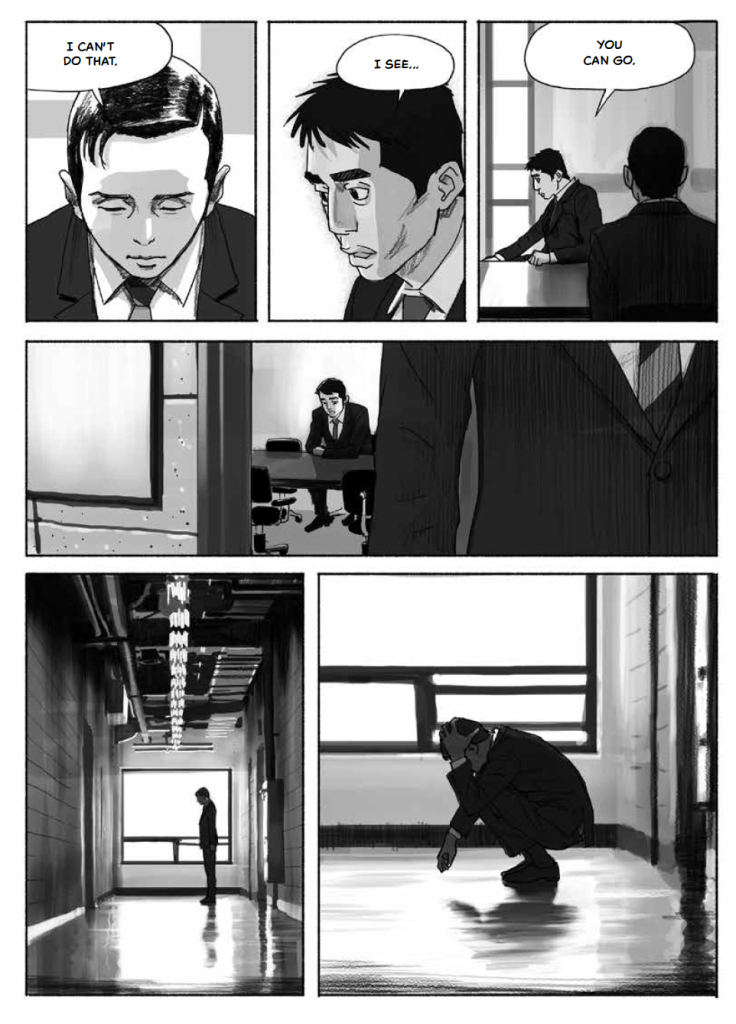

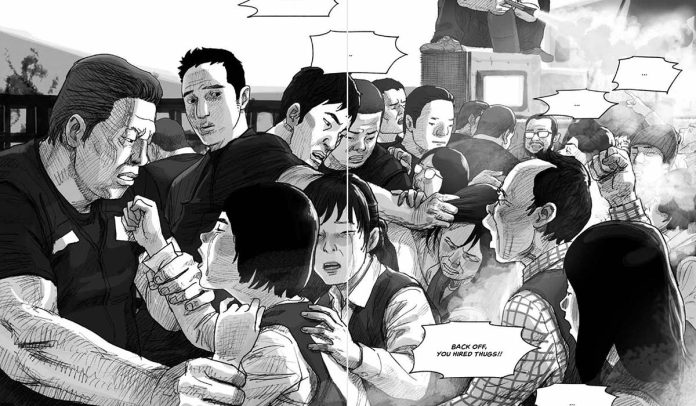

In the first volume of The Awl, Choi depicts a distinctly unglamorous setting that feels gut-wrenching because the cruelty endured by workers are depicted as everyday occurrences. Workers, whether they’re stocking produce at a supermarket, delivering food, hauling trash, working on a construction site, or sewing clothing in a factory, male, female, old or young – they’re subject to the mostly profit-driven whims of business owners and company management. One day employees may be doing their job as usual, the next day, they might be out of a job, injured, or have to endure workplace harassment with seemingly no recourse or relief in sight.

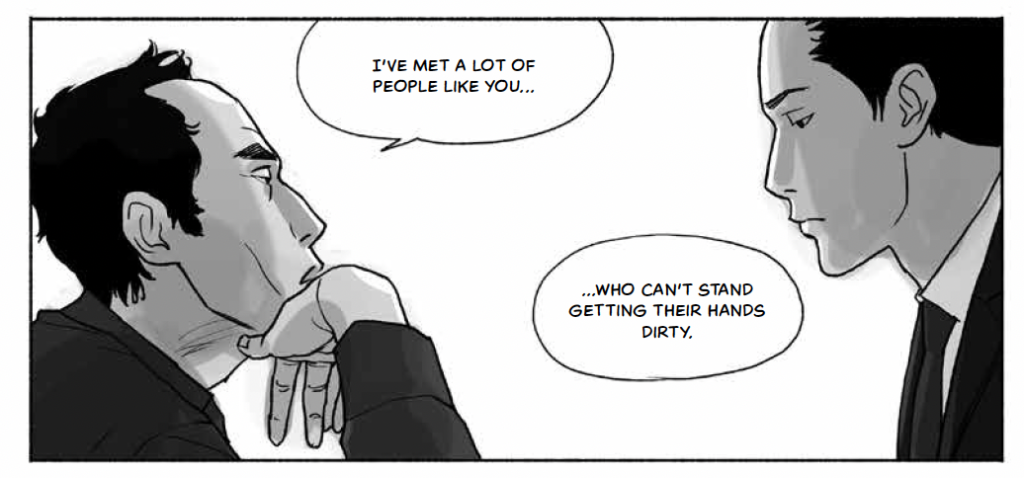

But as in North America, there are labor laws and regulations that are there to protect South Korean workers’ interests. In this story, the person who’s on the workers’ side is Gu Go-Shin, a no-nonsense labor activist who is the director at a labor counseling center. Armed with his knowledge of labor laws, his connections with labor unions and sometimes, just his street smarts, Go-shin offers relief, and a bit of hope to workers who are the end of their rope.

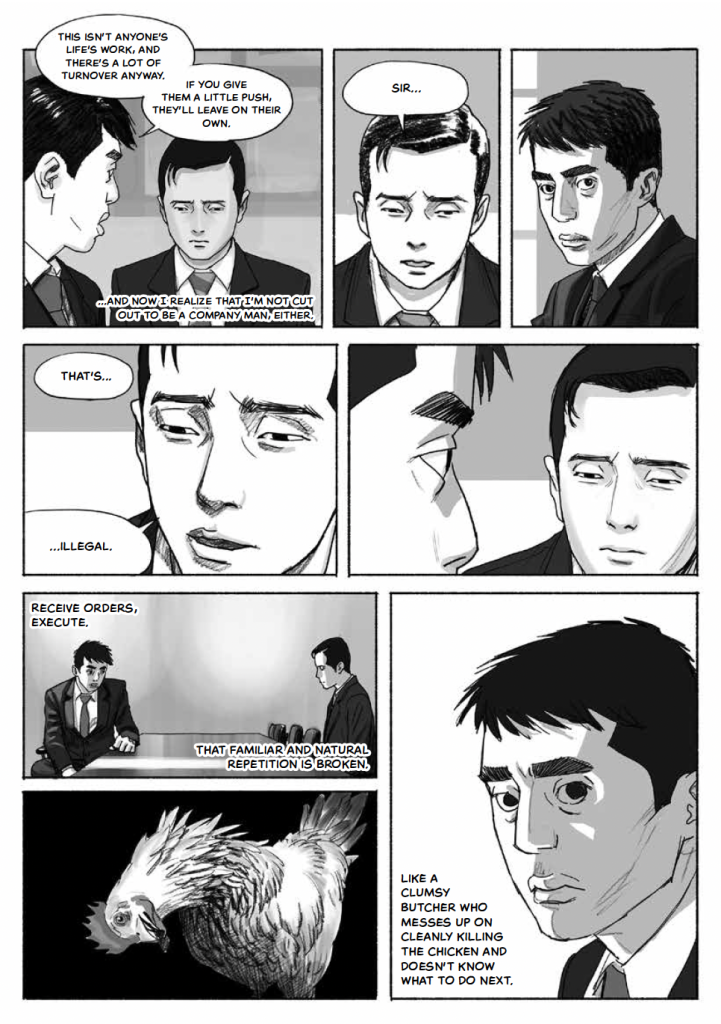

The counterpart to Go-shin is Lee Soo-in, a young man who is a manager at a French-owned supermarket chain. When he is asked by higher-ups to bully his employees to leave their jobs voluntarily, Soo-in struggles, because he finds this order to be morally unacceptable. But if he refuses, he too will be out of a job. After enduring some workplace harassment from managers and colleagues, Soo-in meets Go-shin, who shows him first-hand what it means to fight on the front lines of the labor movement.

To commemorate the print release of the first volume of The Awl, KComicsBeat reached out to Ablaze, who helped arrange this Q&A with Choi Gyu-seok. We talked about his comics, the research he did to write this story, and how issues of the labor movement impact comics creators in S. Korea and perhaps abroad as well.

DEB AOKI: Thanks for taking the time to answer my questions. I read volume 1 of The Awl and was really impressed by your visual storytelling. One thing I noticed as I read the first volume of The Awl is that it’s formatted as regular 2-page spreads. Was this story originally serialized in a printed comic or general interest magazine? Or was it originally drawn in scrolling webtoon format and re-formatted for print?

CHOI GYU-SEOK: It was serialized on Naver WEBTOON, a webtoon platform in S. Korea. (NOTE: The Awl is not currently available in English on WEBTOON US) It’s also my first webtoon work. I’m an artist who has been working on paperbacks, so I composed this story in a paperback format then reorganized it to fit the scrolling format when I posted it on the web.

AOKI: What kind of research did you do to create this story? The scenarios about the supermarket, the delivery person, and the clothing factory feel very real. Are these scenes in The Awl based on real incidents or interviews you did with people who experienced these things on the front lines of the labor movement in S. Korea?

CHOI: I did a lot of interviews in between working on other projects. I think I was doing interviews for about five years. Most of the main scenes in the work are based on real events. Based on interviews with multiple people, we built a single storyline. The interviewees seemed to have themselves met more than a hundred people, ranging from senior union activists to corporate union activists, rank-and-file union members, and current and former workers, and shared those experiences too.

AOKI: I know this story was originally serialized from 2013-2017, and is set in contemporary S. Korea. As I read it, it had me wondering what’s the state of the labor movement in S. Korea today? Is it struggling, or is it getting stronger lately? And why are things the way they are now?

CHOI: The background of The Awl is in the early 2000s, when the Korean labor market was rapidly becoming more flexible. It was serialized in the 2010s. I have some insight into the trends of the labor movement at that time because I have read a lot of data, but I don’t have enough current insight to express my opinion because I am not currently doing comics related to the labor movement.

Based on the impressions I get from the news here, it seems that the connection between the labor movement and the political sphere has weakened, and the leadership of the leading senior labor unions (FKTU – Federation of Korean Trade Unions) has weakened.

AOKI: I appreciated how there’s an interlude in the first part of the first volume that shows Lee Soo-in’s background, including his relationship with his father, his stint in the military and his inner struggle to stand up for what’s right. We also see that his resolve has been beaten down over the years by peers and supervisors who look the other way when corruption and injustice was right in front of them. Both Soo-in and the labor organizer Gu Go-shin are very compelling, complex personalities. Can you share some of the thought process that went into developing these two characters? Which of the two men do you relate to more, and why?

CHOI: The initial process of convincing the reader is quite long. Since the sensibilities of the general reader are far from those who are deeply involved in the labor movement, it was a means to close the gap and also a process to convince myself about who Lee Soo-in is, and his values.

Gu Go-shin is a character who is revered by readers, but Lee Soo-in is a character who the reader relates to, so of course I sympathize with Lee Soo-in. He’s a deontological and liberal person. (NOTE: In deontological ethics, actions should be based on moral imperatives or what one believes is right, regardless of the end result.)

On the other hand, Gu Go-shin has a strong teleological tendency. (NOTE: Teleological refers to starting from the end and reasoning back, explaining things based on their end purpose, or basically “everything happens for a reason.”)

In the beginning, the two are like master and disciple, but at some point, the fundamental differences between the two characters are revealed, and this becomes the subject that drives the second half of the story.

AOKI: As you read The Awl, you can’t help but feel angry at what the workers go through. Did readers in S. Korea feel the same way? For example, did this story, both the webtoon and the live-action drama version, have an impact on workers’ rights and awareness of unionization issues with the general public in S. Korea? Did it inspire political or social change?

CHOI: I don’t know how it affected the public, but I remember that while the work was being serialized, dramatized, and aired, there were a lot of media articles about the events and people that inspired the work. There was also a comment that the children of union leaders were able to understand their parents. I’ve met readers who said they had formed a union after reading the manhwa or had a job in the political arena.

I feel that there have been more comics and media that deal with social issues in a more detailed and direct way since The Awl. I don’t know if it was the effect of The Awl or just because it was the right time, but I like to believe it was the former.

AOKI: In the United States, there’s also struggles related to the labor movement, from companies and industries big and small — including many comics publishers / comics-related companies dealing with their employees seeking to get union protections in their workplaces.

Many S. Korean webtoon artists mention their grueling work schedule producing weekly webtoon chapters in some of their author’s notes during hiatuses or after a series is finished. Are you seeing similar sentiments on the S. Korea webtoon publishing business about unionization or establishing standards for workers / creators’ rights? If so, can you share any examples? And if not, why do you think that’s something that S. Korean webtoon creators / publishers aren’t very concerned about at this time?

CHOI: I know that there are associations for creators and manga artists, and that unions have been formed. Of course, wage earners and artists who own their works have different legal statuses, so it seems to be different from the general form of labor unions. Weekly serialization and harsh workloads are decades-old, entrenched patterns in East Asian comics publishing, so I’m ambivalent. As a reader, I hope that interesting works will come out often, and as a writer, I lament that it is an inhumane method.

Cartoonist groups and related companies are constantly discussing solutions, but I don’t know if there will be a solution that satisfies everyone. It’s a structure created by readers and writers together, and you can’t force a writer who is brimming with creative enthusiasm to do a little work. It’s a difficult problem.

However, just as a group of artists, despite economic difficulties at a time of destruction for the Korean comic publishing market, created the beginning of the current webtoon industry, I believe that the creators’ new attempts and courage will find a way that can benefit writers, readers, and companies.

AOKI: The Awl is the second of your works published in English — the other being The Hellbound (published by Dark Horse). You have many other works that are currently only available in Korean — which one do you think readers / publishers should pick up next for publication here, and why?

CHOI: I understand that 100℃ (백도씨) was also published in English. So, this is the third one.

(NOTE: 100℃: South Korea’s 1987 Democracy Movement was published in 2023 by University of Hawaii Press, with his name spelled as “Choi Kyu-sok,” which probably explains why it wasn’t easy to find online.)

South Korea’s 1987 Democracy Movement

)

Many of my works are based specifically on Korean society and events, so it would be difficult to introduce them overseas. If I had to pick one, I would like to be The Natives of the Republic of Korea (대한민국 원주민, available in Korean from Changbi Publishing) This is a short book that depicts Korea from my father’s childhood to my youth, through family interviews. I think it’s a good book to look into the rapidly changing Korean society.

AOKI: What are you working on now, comics wise?

CHOI: We are currently finishing the Season 2 serialization of The Hellbound, and I’m doing additional works for publication. For the time being, I’m going to work on a short story to research a new style.

The Awl Volume 1 is available now from Ablaze, in print and digital formats.

[…] una historia sobre fe y creencias, los temas que le han interesado durante mucho tiempo”, Choi ((El awl) le dijo a Netflix. “Estaba intrigado y pensé que podríamos encontrar una historia […]