Here at KComics Beat, one of the driving missions for the site is to put Korean comics into context and lift the veil of mystery that surrounds them compared to the decades of visibility and research that similar mediums have enjoyed in the US and abroad. KComics Beat contributor Adam Wescott recently took to Otakon 2024 to detail a unique panel in “The World of Korean Educational Manhwa and its History” that centered on the history of Korean educational manhwa, a comics medium that has gone through its own trials and tribulations over the past 60 years. — Managing Editor Humberto Saabedra

From the success of the Solo Leveling anime series to WEBTOON Entertainment going public this June, 2024 has been a breakout year for the Korean webtoon as a medium. Yet English-language coverage of the history of Korean comics (or “manhwa”) remains scarce. Any comic published before the 2014 debut of WEBTOON in the United States market may as well be a dinosaur; print manhwa is dust. Only a handful of English-language works, such as John Lent’s Asian Comics, addresses manhwa within its proper historical context. (As an aside, keep an eye out for Lent’s Comics Art in Korea due early next year.)

“The World of Korean Educational Manhwa and its History,” a panel staged this year at Otakon in 2024, sought to address this knowledge deficiency. Manhwa artist Moon Inho and cultural educator Park Seulki Rhea acknowledged that webtoons are a defining force in South Korean comics. But they came to Otakon discuss an entirely different field: educational manhwa, a genre of comics that is popular in Korea but practically unknown in the United States.

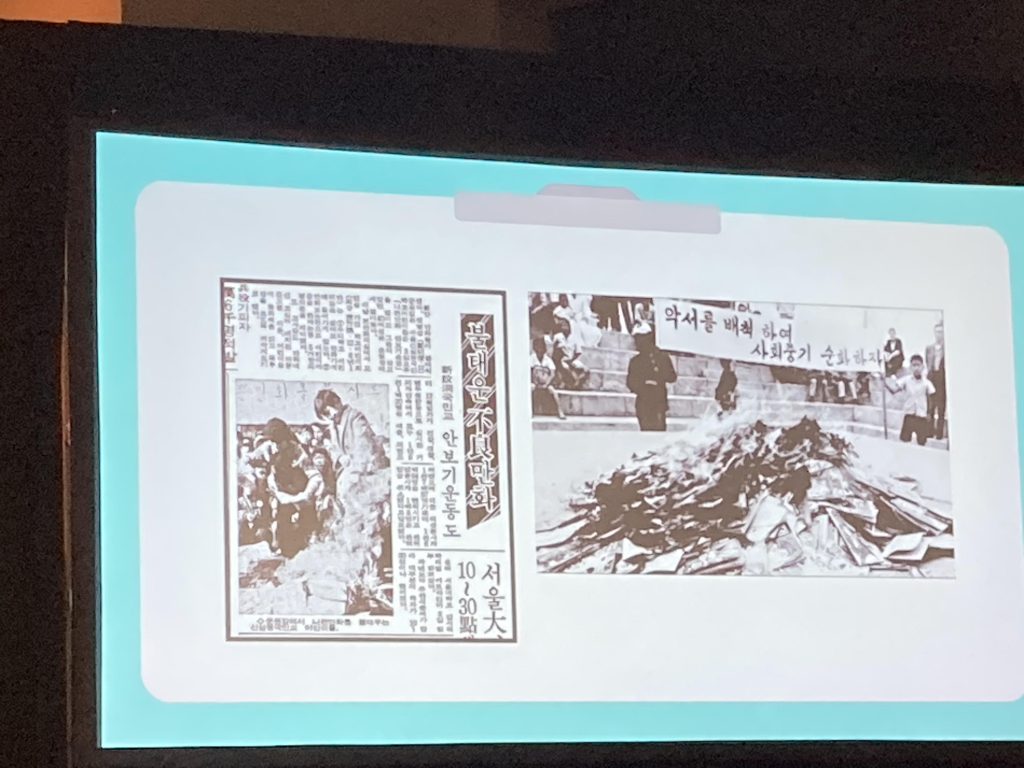

Before cellphones existed, before the rise of WEBTOON, there was print manhwa. People drew and read these comics because that is what people have always done. But it wasn’t easy. The military dictatorship of the 1960s, said Moon, despised manhwa as degenerate literature. In 1967 they declared manhwa one of the “six major evils” alongside tax evasion, gambling, drugs, violence and smuggling. It was despised by many adults and absolutely forbidden to children.

Educational manhwa was the exception to the rule. If comics served a useful function by teaching children important lessons, they couldn’t possibly be degenerate, right? As a result of the distinction and marketing, parents bought educational manhwa for their children. Libraries around the country also acquired educational manhwa even as they rejected other kinds of non-educational manhwa. As can be expected of such a collective drive, the children themselves never had much say in the matter, owing to cultural expectations and societal norms. Educational manhwa was advertised to their parents, not to children directly. But that, said Moon, is how educational manhwa was able to survive.

Despite this, the medium remained a frequent target of government and other forms of censorship. For example, nudity was a common concern and other complaints could be even more extreme. A 1976 series about a poor family was blasted for being “too entertaining” (it had puns, of all things.) Another children’s comic starred creatures like dinosaurs, ostriches and aliens so as not to encourage child readers to see themselves in the mischievous characters.

According to Park, people believed at the time that if you gave children the same authority as adults, then adults would have less authority. As a result, children were rarely portrayed realistically in the pages of manhwa at this time and their problems were not directly acknowledged. The depiction of parental abuse was forbidden in educational manga and government censors hoped that by denying the truth of society in art, they could enforce their own truth upon the artists and readers of South Korea.

Moon and Park insisted, though, that these qualities were not exclusive to South Korea and Park even drew a comparison to the birth of the Comics Code in the United States. The Seduction of the Innocent, a book by Fredric Wertham published in 1954, insisted that comics were an increasinbly poor influence on young people. As a result, the Comics Code Authority was formed to crack down on what was at that time a developing and thriving medium. In the pages of Batman, said Park, the Joker was transformed from a terrorist into a man who changed water into jelly. Other comics that starred women and black people fared worse–they were erased.

Manhwa in South Korea has transformed since then. One reason for this was the mass pro-democracy protests against the government of that time. (You can learn more about this history in the excellent children’s comic Banned Book Club.) Another was the influence of manga, which found its way into the Korean pirate markets despite strict regulations forbidding Japanese culture at the time. Moon remembers finding Dragon Ball as a child in an issue of the Korean magazine IQ Jump. Manga overcame censorship in Japan thanks to the efforts of artists like Go Nagai in the 1960s and 70s. It was so popular that South Korea finally lifted the ban on Japanese culture in 1998, with its positive effects continuing to this day.

Japanese manga’s entry into the South Korean market combined with the 1997 economic crisis nearly obliterated the South Korean manhwa industry. It was educational manhwa, says Moon, that stepped into the gap to save the medium from total destruction. These comics were no longer didactic instruction manuals for children. Educational manhwa artists now sought to deliver information to young readers in an entertaining way and were successful as a result.

Some of these comics were explicitly instructional. One example was the Why? Series, which covered topics including history, science and the lives of famous people. Another example was the Survival series, which depicted children surviving such phenomena as insects, dinosaurs and volcano eruptions. These books united facts with the appeal of danger, a foolproof method for capturing the attention of young children.

Other educational manhwa utilized myth and legend as an educational tool. One of the biggest early successes in educational manhwa, Moon said, was a series based on the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West. (Dragon Ball loosely adapts this story as well.) The Greek and Roman Myths in Comics was also very popular. It was adapted into an animated series called Olympus Guardian that ran from 2002 to 2003.

Educational manhwa continues to evolve to this day in Korea. There are manhwa about Youtubers, and manhwa about esports stars like League of Legends player FAKER. Moon himself drew a comic crossover starring characters from popular video games. There are even educational manhwa like The Golf Guide for Dummies which might appeal to adults rather than children. Webtoons might have the spotlight for now. But educational manhwa, said Moon and Park, truly has no limit.

To close this out, Otakon has been a hub for anime and manga fandom throughout the years and Korean manhwa fandom with the increased presence of Korean culture this year was a definite sea change. At the same time, I am grateful that Moon and Park took the time to educate us in the history of their chosen medium. Educational manhwa artists navigated government dictatorship, an imploding market and the evolving comics medium itself to build a beloved institution in their home country. They deserve recognition and appreciation outside of Korea.