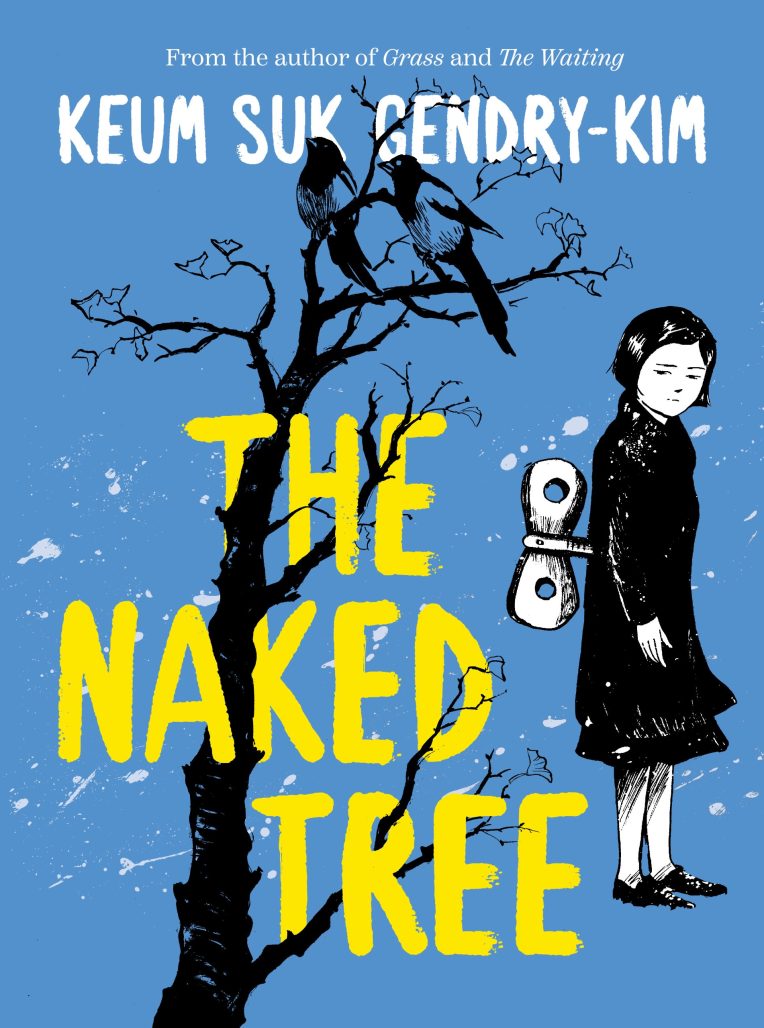

In Harvey Award-winning Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s graphic novels (GRASS, THE WAITING), the Korean war provides a rich tapestry in which to explore the plight of women and social class. In THE NAKED TREE, Gendry-Kim continues this narrative with her visually stunning adaptation of Park Wan Suh’s classic coming-of-age novel, mixing history and fiction with emotional immediacy and artistic finesse.

Taking place in 1951, the story finds 20-year-old Lee Kyeonga scraping together a living in war-torn Seoul as a salesperson at the Post Exchange. By day, she sells handkerchiefs decorated with hand-painted portraits to American soldiers. By night, Kyeonga suffers in misery in a shabby shack with her mother, who mourns the loss of her two oldest brothers during a bombing attack at the home. When married artist Park Su-geun takes on a job as painter at the Post Exchange, Kyeonga finds herself drawn to him and uses her tryst with the painter in a quest to liberate herself from her circumstances. In Gendry-Kim’s hands, The Naked Tree is devastating and powerful, a haunting portrait of the aftermath of war and its trauma on survivors.

Gendry-Kim offers her thoughts on her role as documentarian and spokesperson for women’s rights in an interview conducted in and translated from French. She also elaborates on how she approached recreating the famous paintings by the influential modernist Park Su-geun, whose depictions of Korean daily life launched him into post-mortem fame.

NANCY POWELL: Is The Naked Tree the first time you have adapted a prose novel to graphic novel format?

KEUM SUK GENDRY-KIM: Indeed it was the first time. After The Naked Tree, I adapted another novel entitled Alexandra Kim: A Woman of Siberia.

POWELL: In the foreword to the book, Ho Won-Sook, the author’s daughter, writes, “it was as though the artist had burrowed into my mother’s soul to bring out the intentions of the original story.” What did this story mean to you as a reader and as an artist?

GENDRY-KIM: I can’t help considering a work written as both a reader and an artist. When I first read this novel, I immediately got under Kyeonga’s (the heroine’s) skin. From the very beginning of the book, I could already see images of scenes in my head. It was so fascinating that I took the time to reread each passage to savor them even more. I really enjoyed adapting this book into a graphic novel, even though the story is painful.

POWELL: What were some of the challenges you found in adapting this novel? And how does the creative process compare with the process you used to create Grass and The Waiting?

GENDRY-KIM: The novel is over 300 pages long. What was difficult was making choices. I had to omit from my graphic novel certain passages that I liked in the novel. On the other hand, I also wanted to add certain elements that were not in the novel.

Grass and The Waiting are based on testimonies (research and encounters) that I gathered. I had total graphic and writing freedom. I could make changes, and I did, right up to the last moment. Just before the book went to print.

For The Naked Tree, even if I had graphic freedom, I had to remain faithful to the novel in outline.

POWELL: Much of the subject matter in these three books – Grass, The Waiting, and The Naked Tree – deals with the post-Korean war aftermath in women’s lives. And yet you’ve only touched the surface of this very important yet understated subject. Do you see yourself as a historian? What is the artist’s role in preserving and interpreting history?

GENDRY-KIM: I don’t consider myself a historian at all. What interested me in these three books was telling the stories of people who lived through the war, so as to avoid repeating the same horrors. In such situations, the plight of women is even worse.

I don’t want to say too much about the role of the artist. But when you meet these people, or you have relatives who have lived through it, or you have lived through it yourself, as an artist you can’t remain silent.

POWELL: How did you discover Park Su-geun’s paintings?

GENDRY-KIM: During my school years, when I was young, I had already seen some of his paintings in books. He is recognized as an artist who painted small, everyday people with simple strokes and thick layers of paint that give a stone-like appearance.

POWELL: How did you approach recreating Park Su-geun’s paintings in the book? And did having a painting background help in that regard?

GENDRY-KIM: I tried to imitate some of his well-known paintings, which necessarily had to be included in this book. I created some “original” ones by imitating his style.

I didn’t want to copy his paintings exactly. But when you see the reproduction, if it’s reminiscent of his paintings, for me it’s a success.

POWELL: In an interview with The Asian American Writer’s Workshop, you spoke of the role of nature as “the most incredible artist.” Autumn and winter play an especially prominent role across the three books. When you go to create a story, do you also consider seasonality into the storyboarding process?

GENDRY-KIM: Of course I do. For me, the seasons are very important in my books. Rain and snow could also mean many things in my scenario. Because all this evokes color, smell, light, time, sound and silence in my books, even if the drawings are in black and white.

POWELL: Which manhwa artists are on your bookshelf now?

GENDRY-KIM: Ma Yeong-shin, Hong Yeong-sik, Ancco and some other manhwaga books not translated into English.

POWELL: Which international comic book artists do you want to read?

GENDRY-KIM: Drawn & Quarterly has published Fujiwara Maki. But not in Korean yet. I’m curious to read it. And I want to read the more recent books by Joe Sacco, Kate Beaton and many other superb authors, but unfortunately, it’s difficult to find them in Korean.

POWELL: And if you were to translate an international comic book into Korean, which would it be?

GENDRY-KIM: Dirty Plotte: The Complete Julie Doucet by Julie Doucet.

The Naked Tree is available from your local bookstore and/or public library now.